Links to This Note

- Nothing here yet...

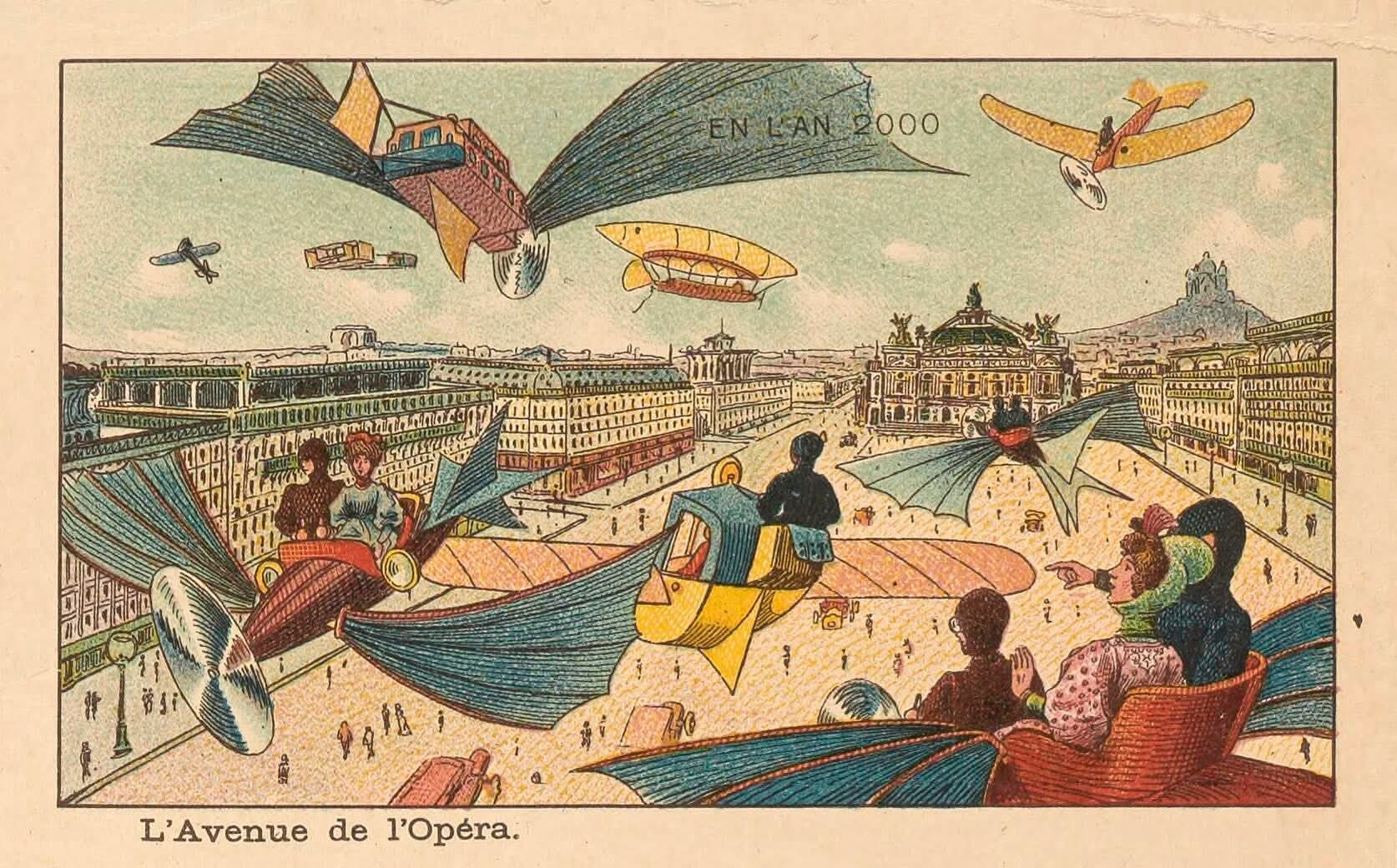

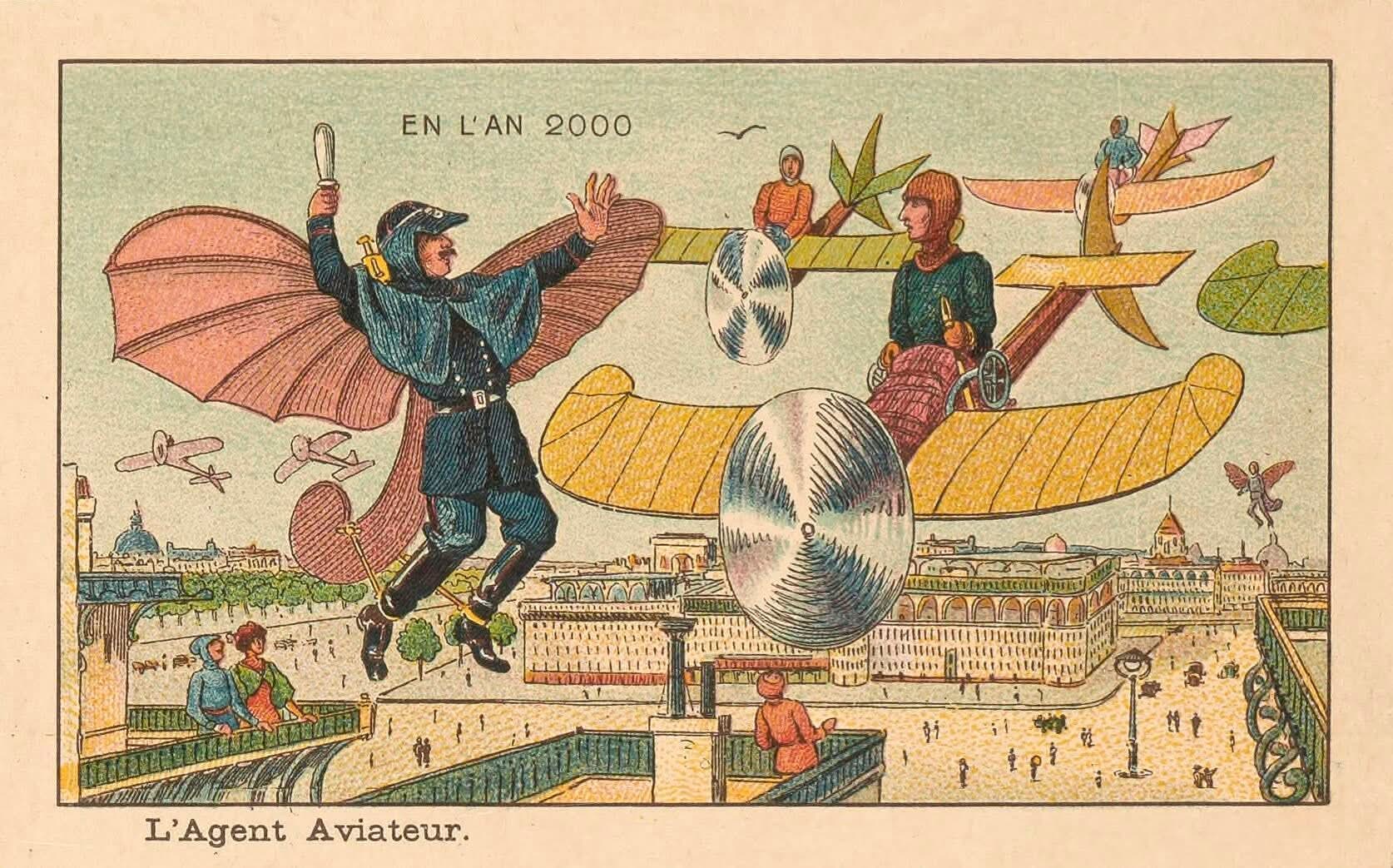

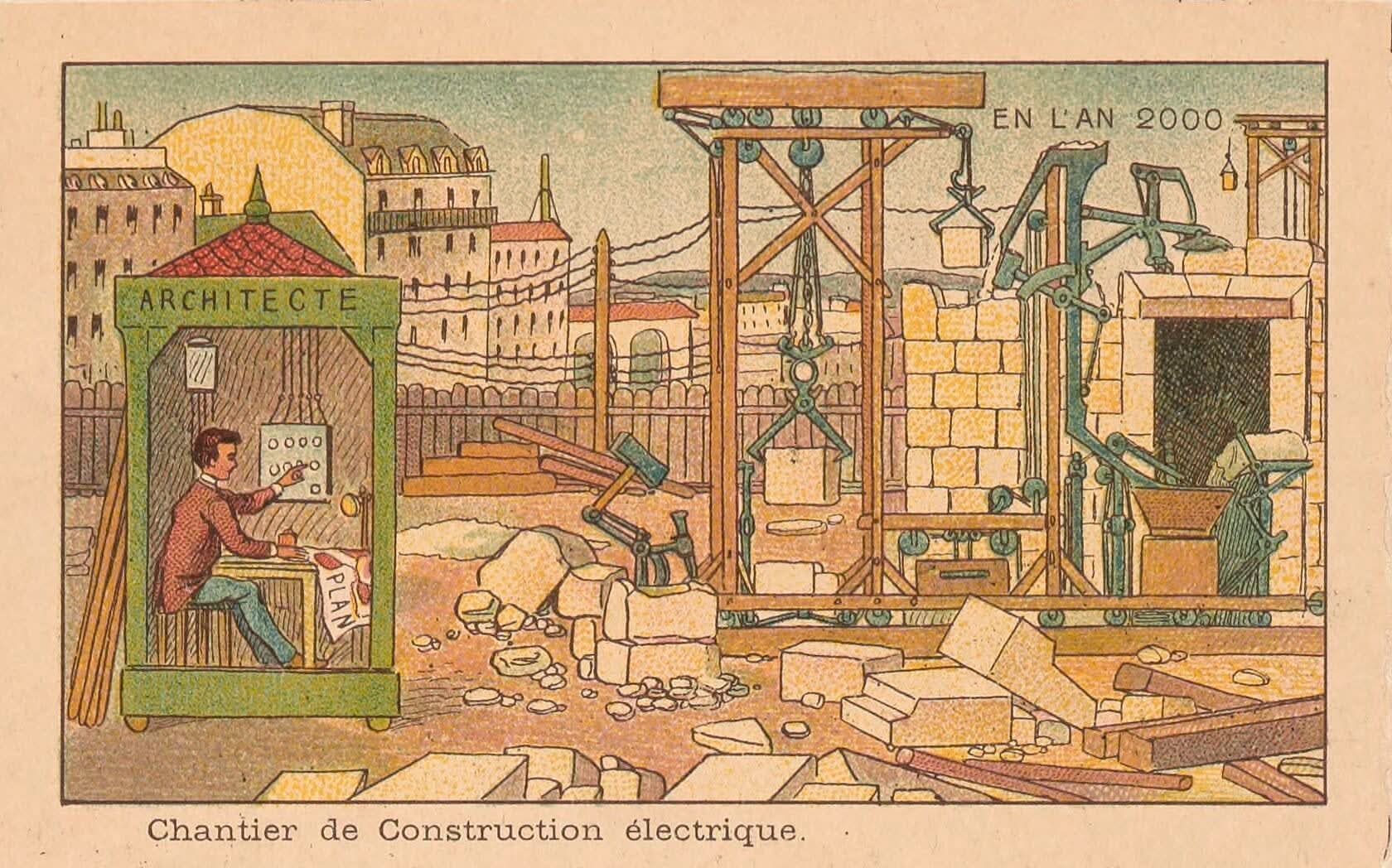

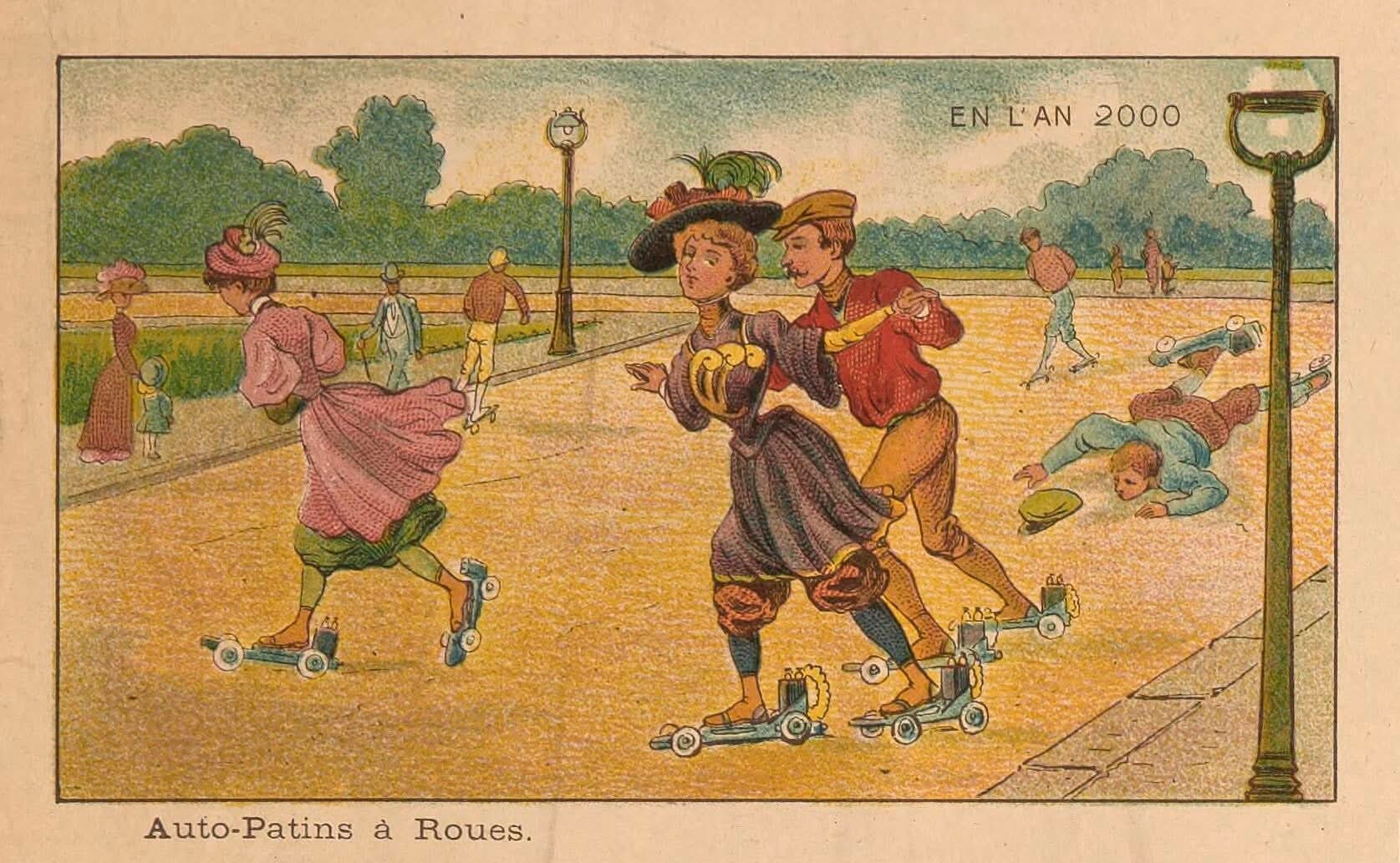

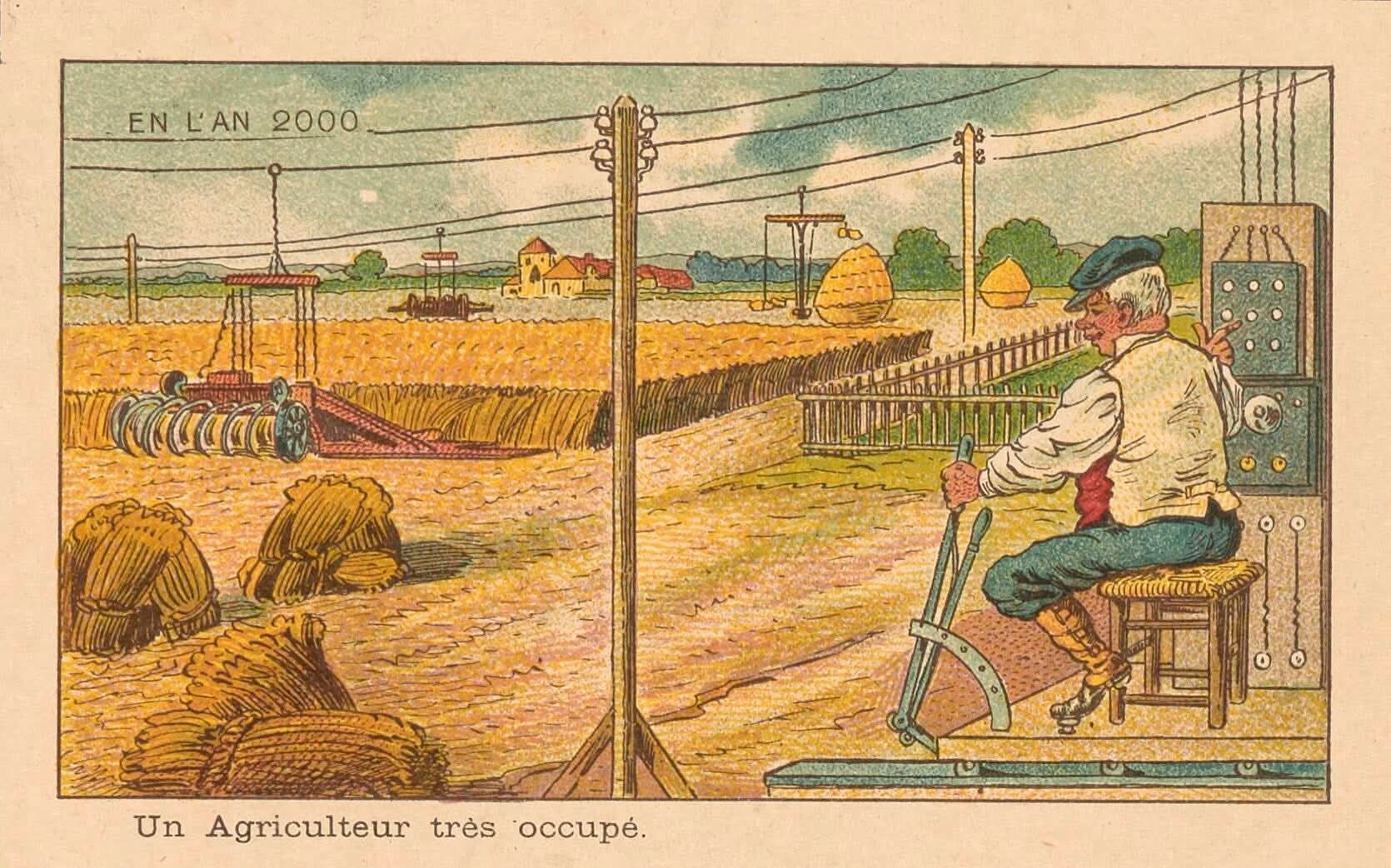

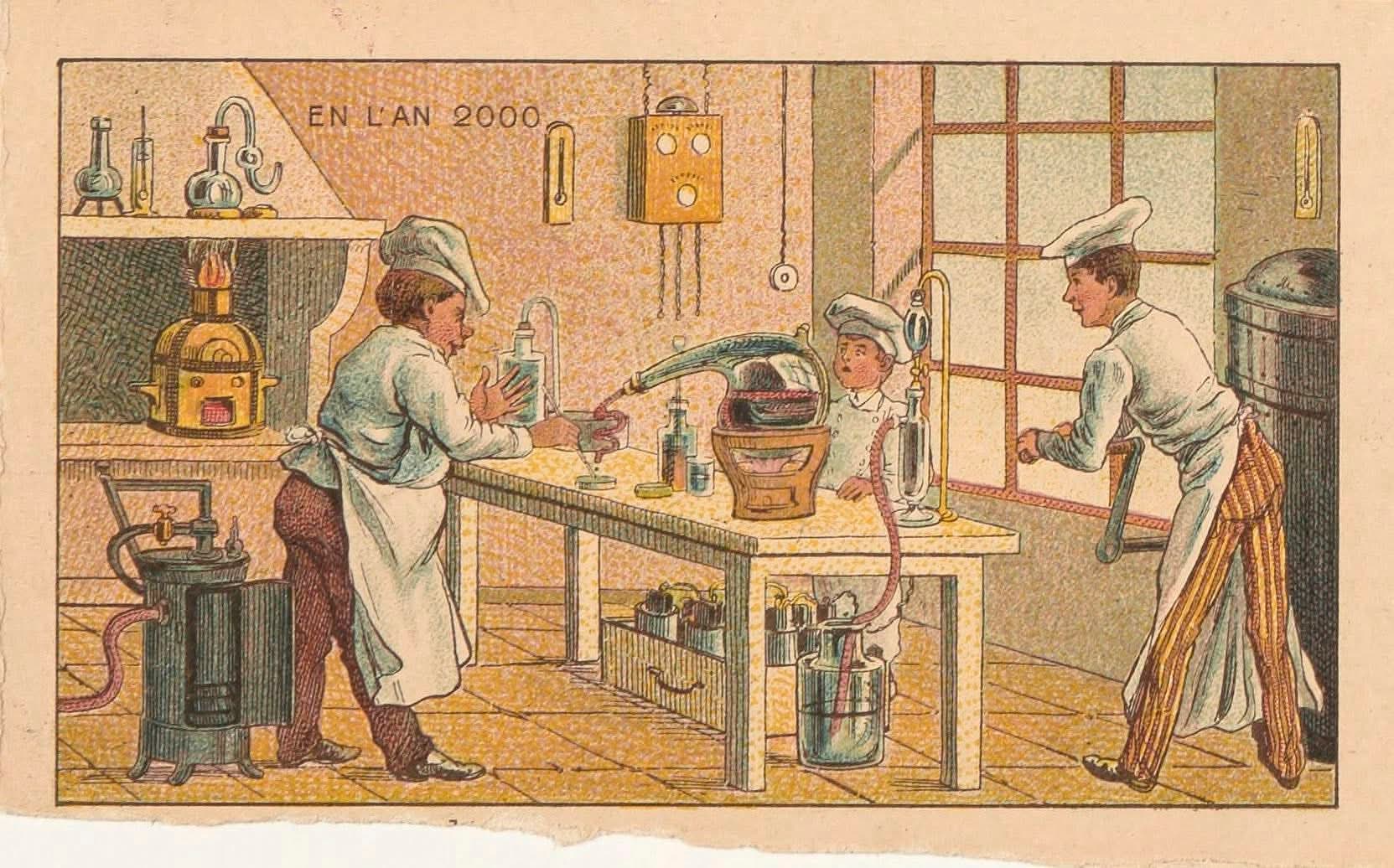

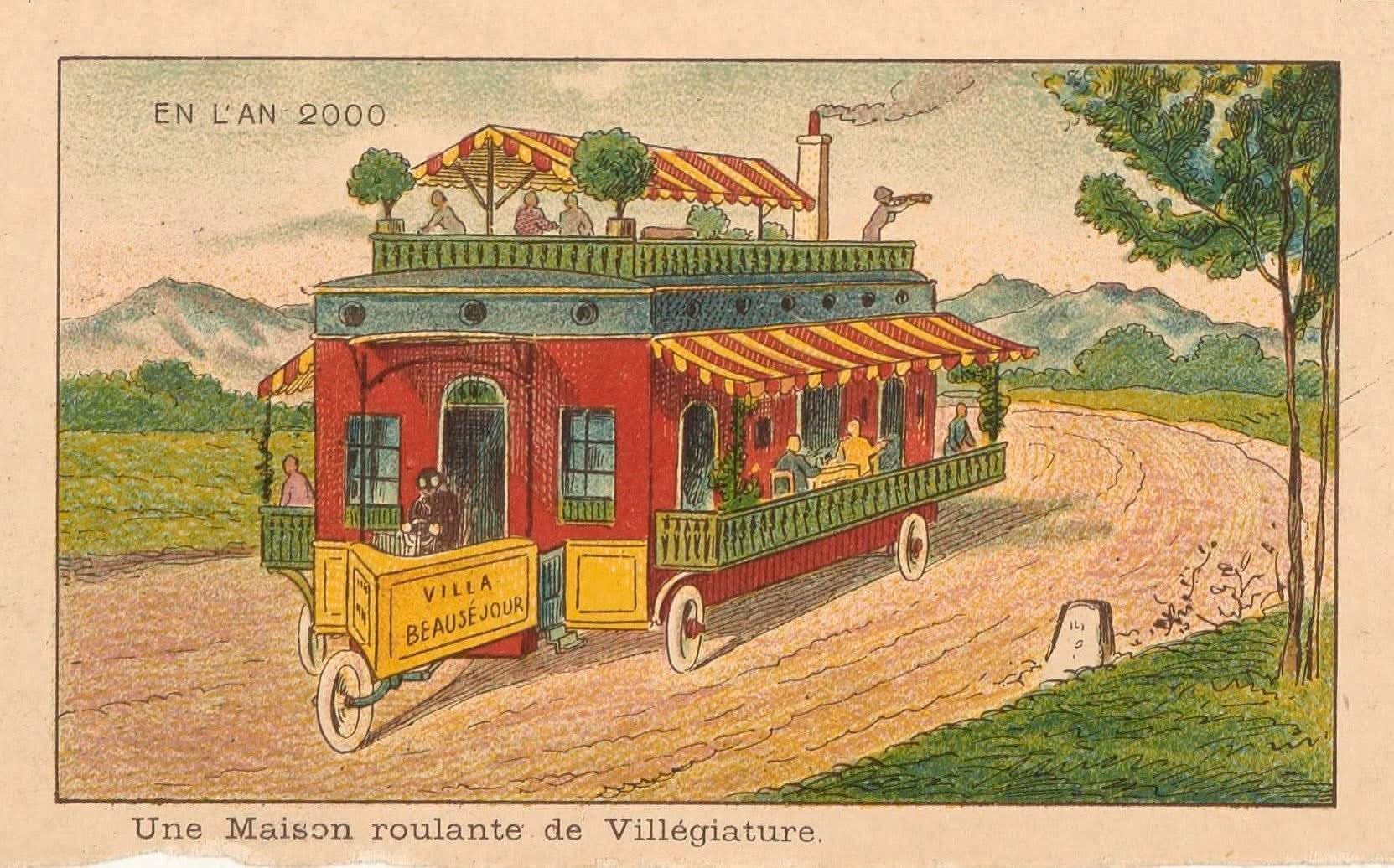

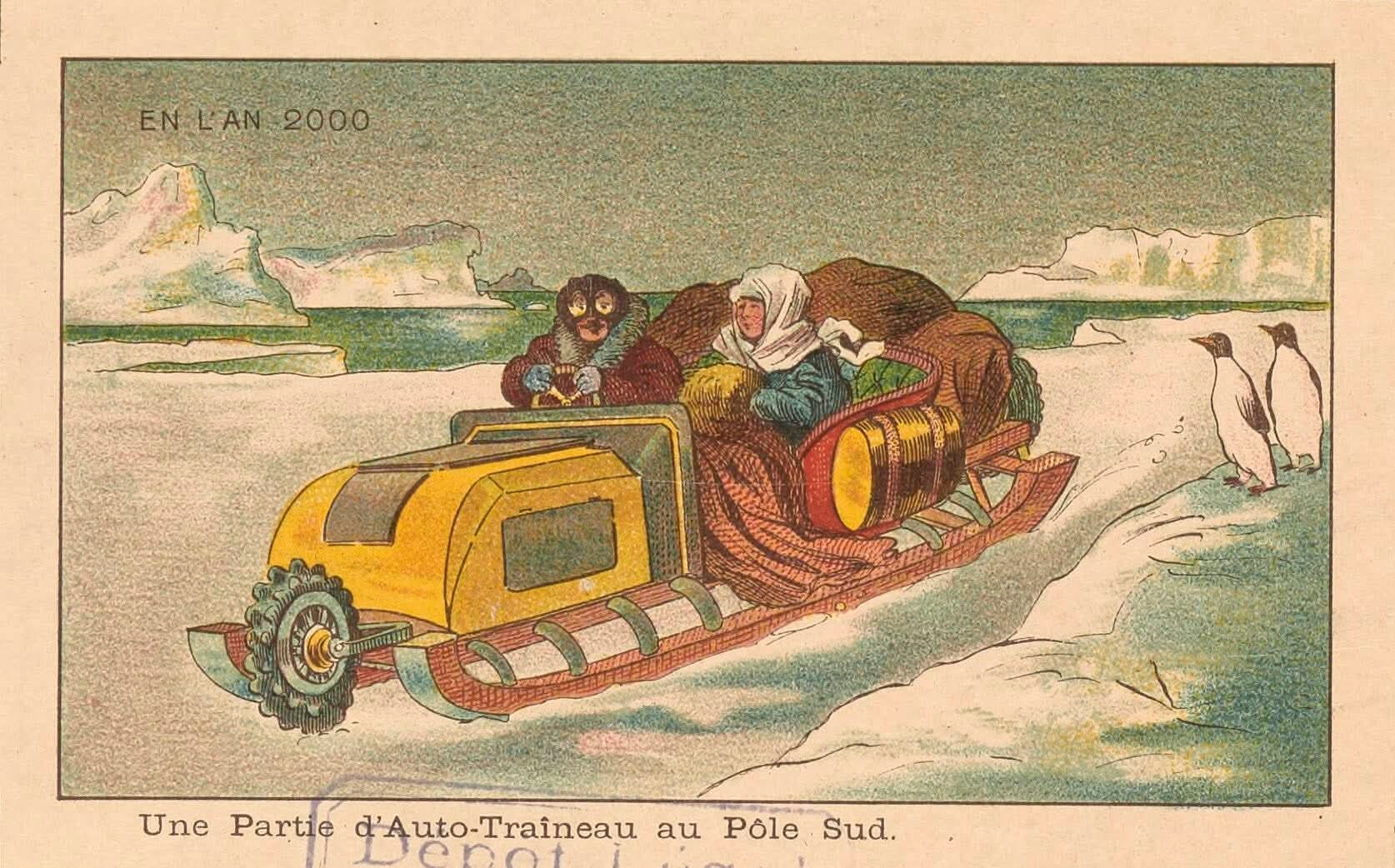

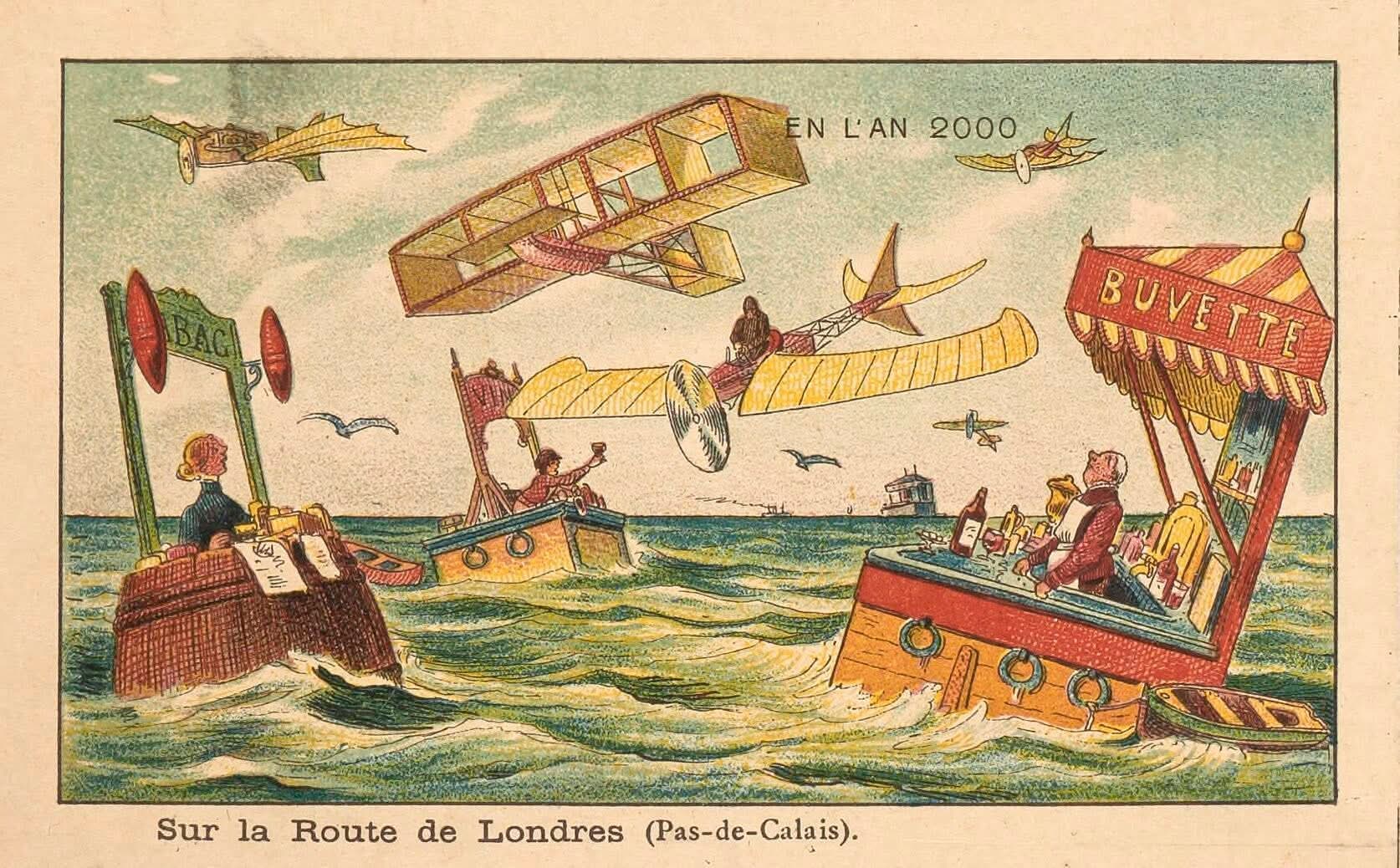

Lost Futures: A 19th-Century Vision of the Year 2000

Lost Futures: A 19th-Century Vision of the Year 2000 - The Public Domain Review

- English

- 한국어

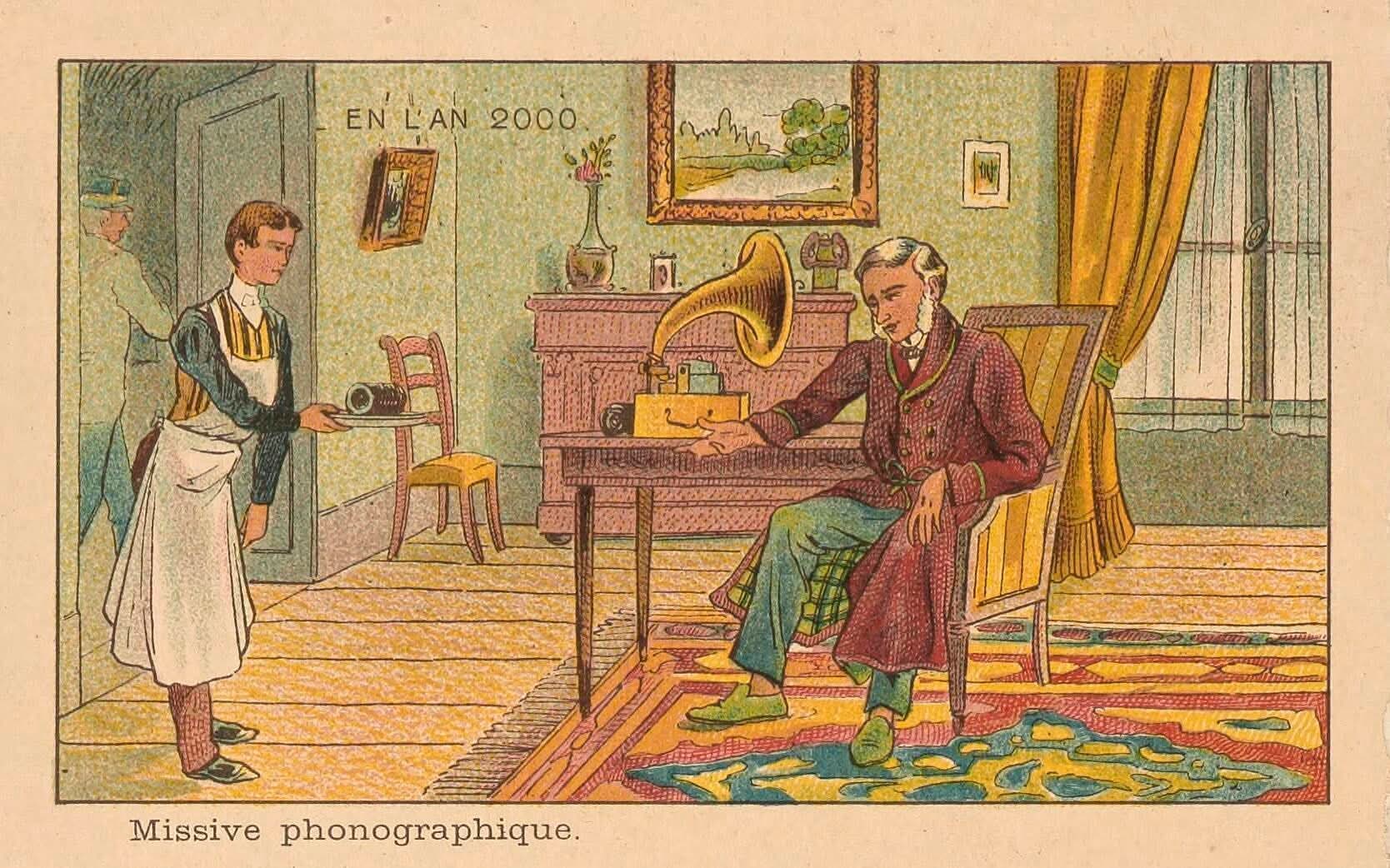

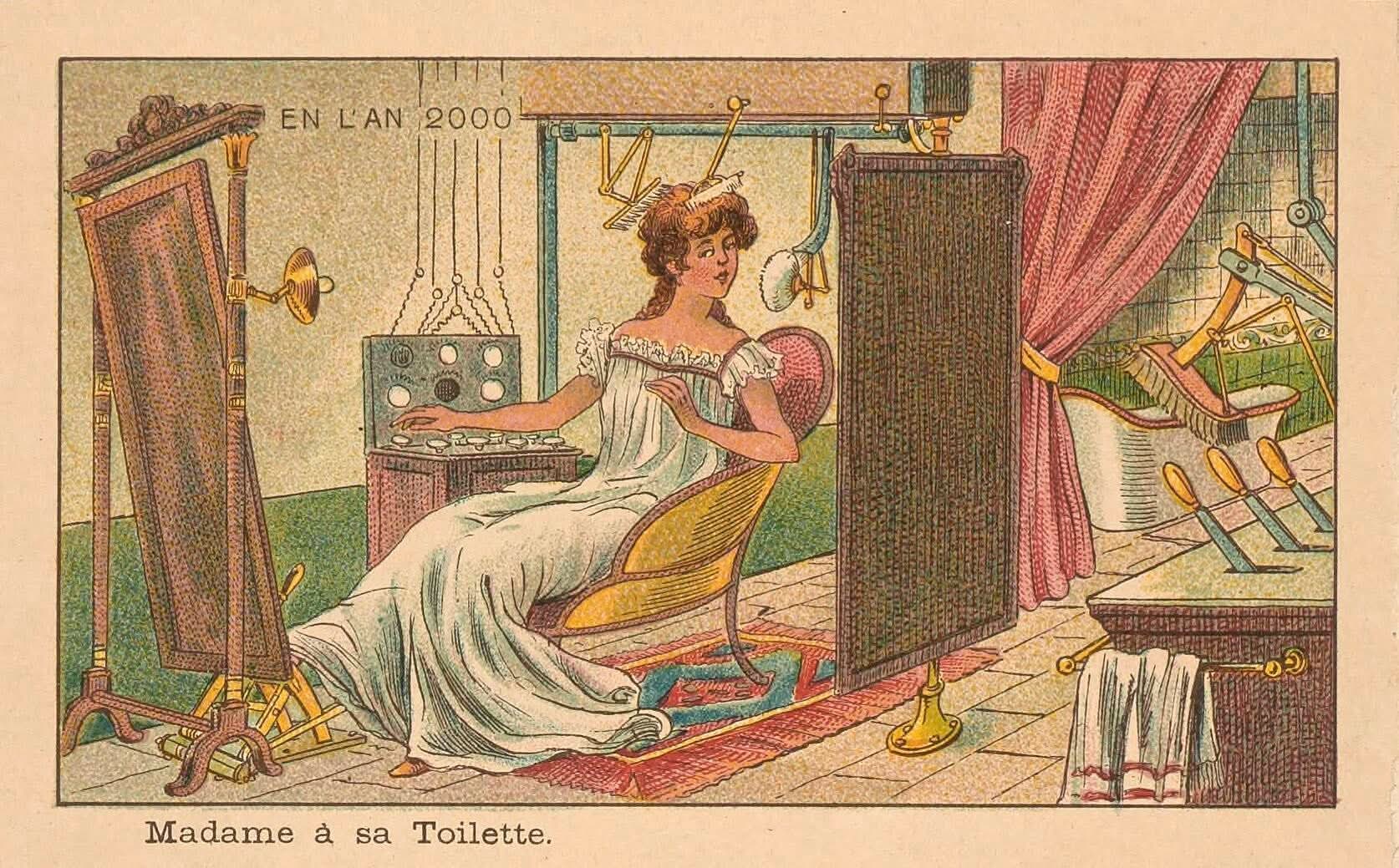

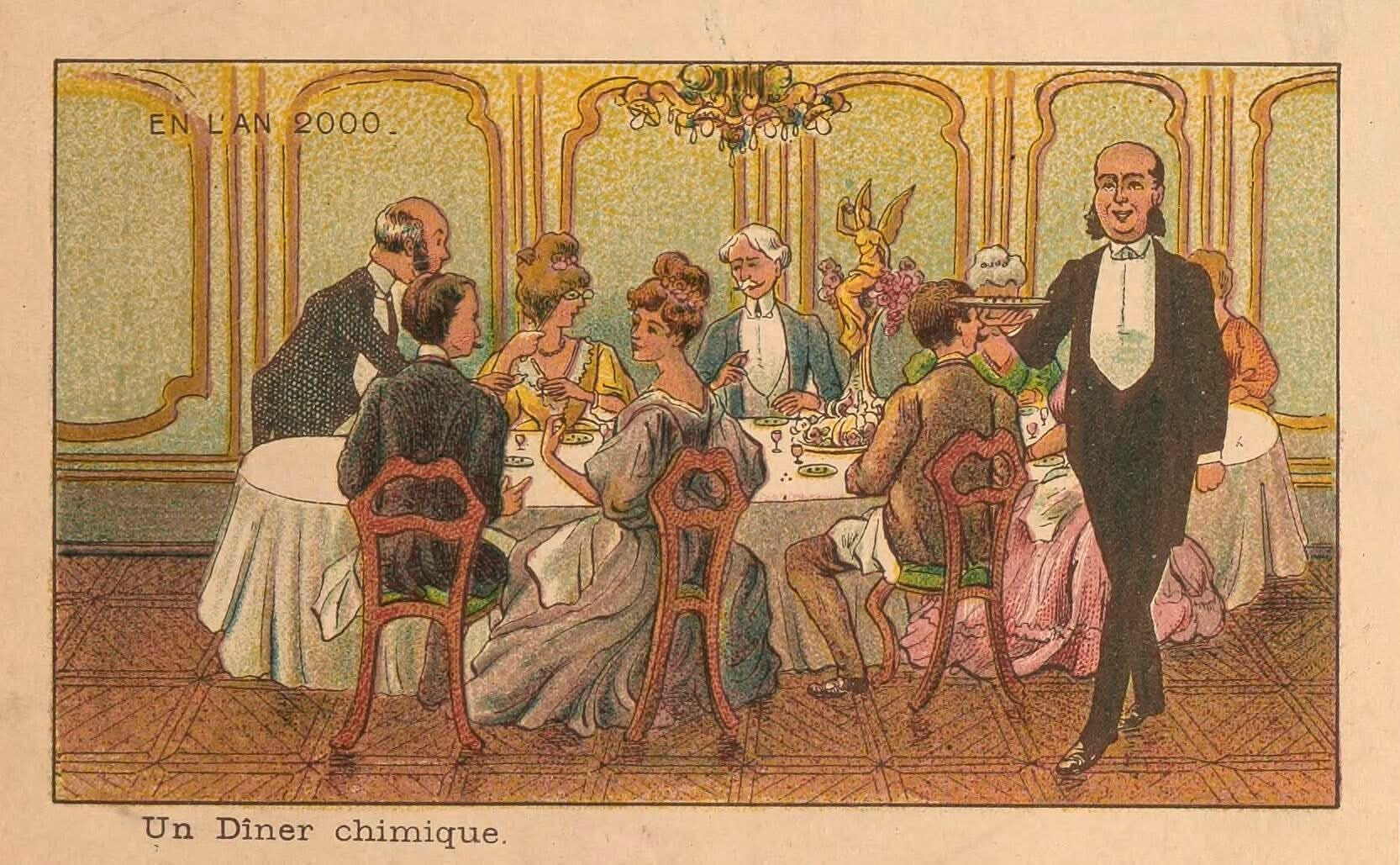

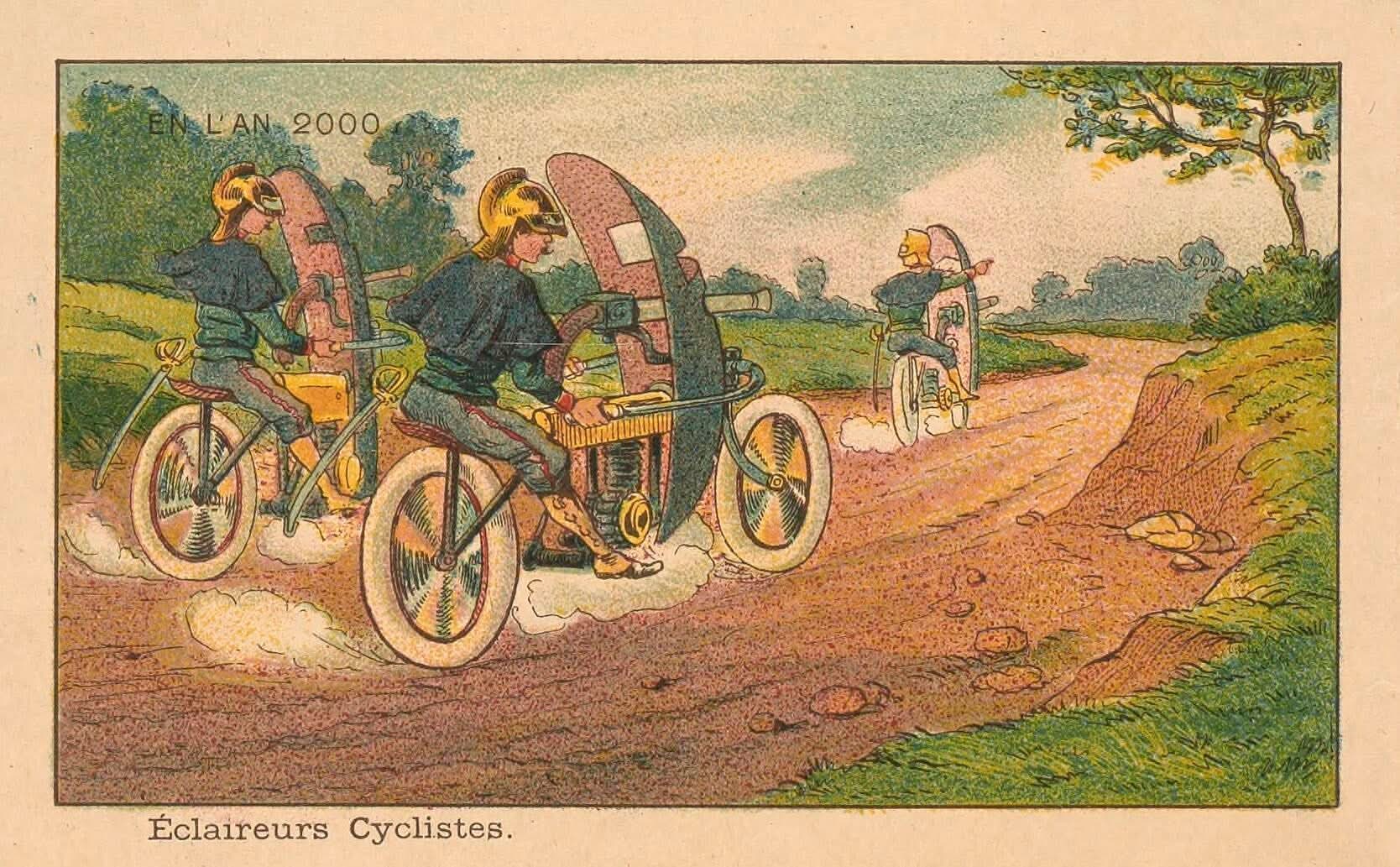

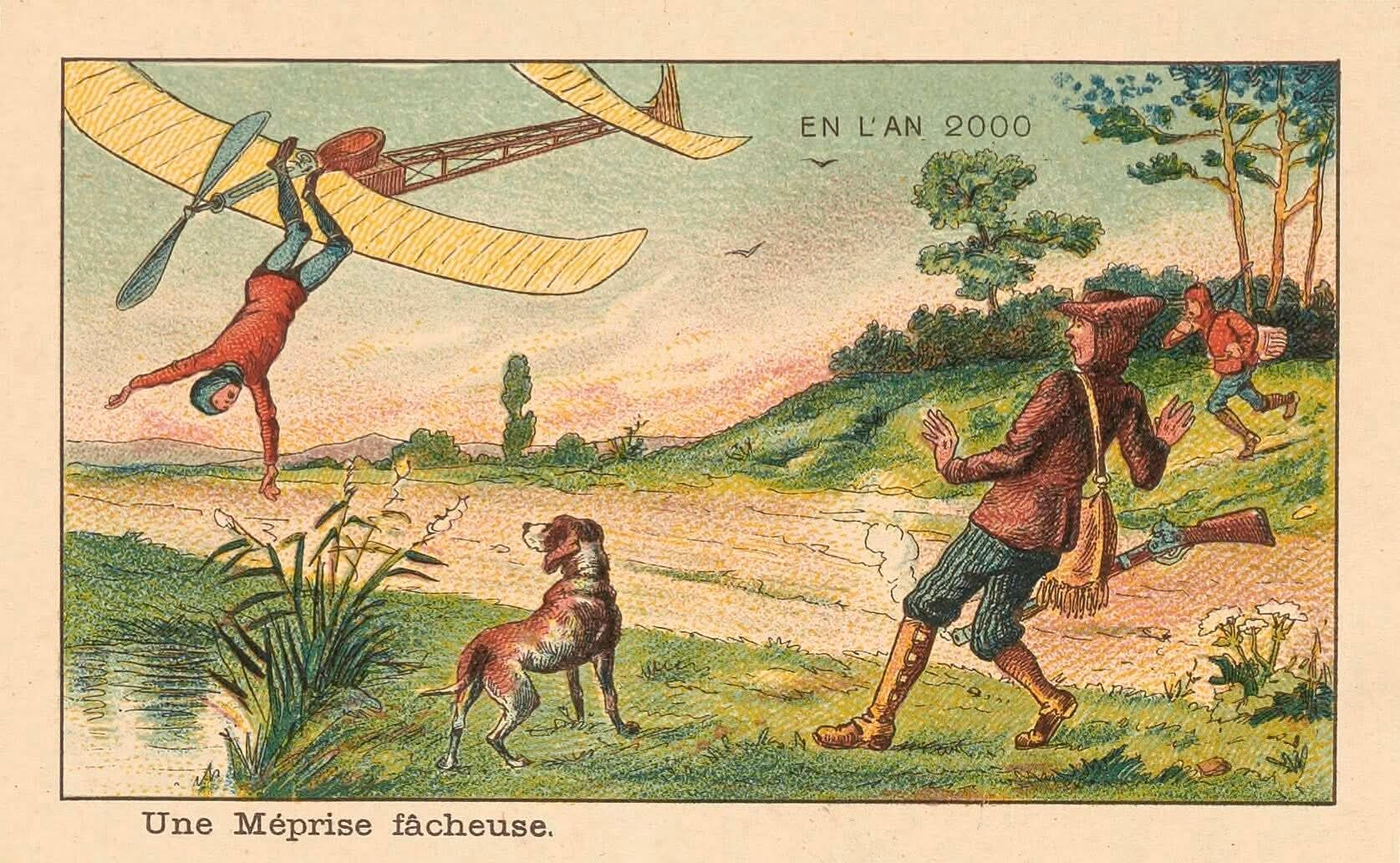

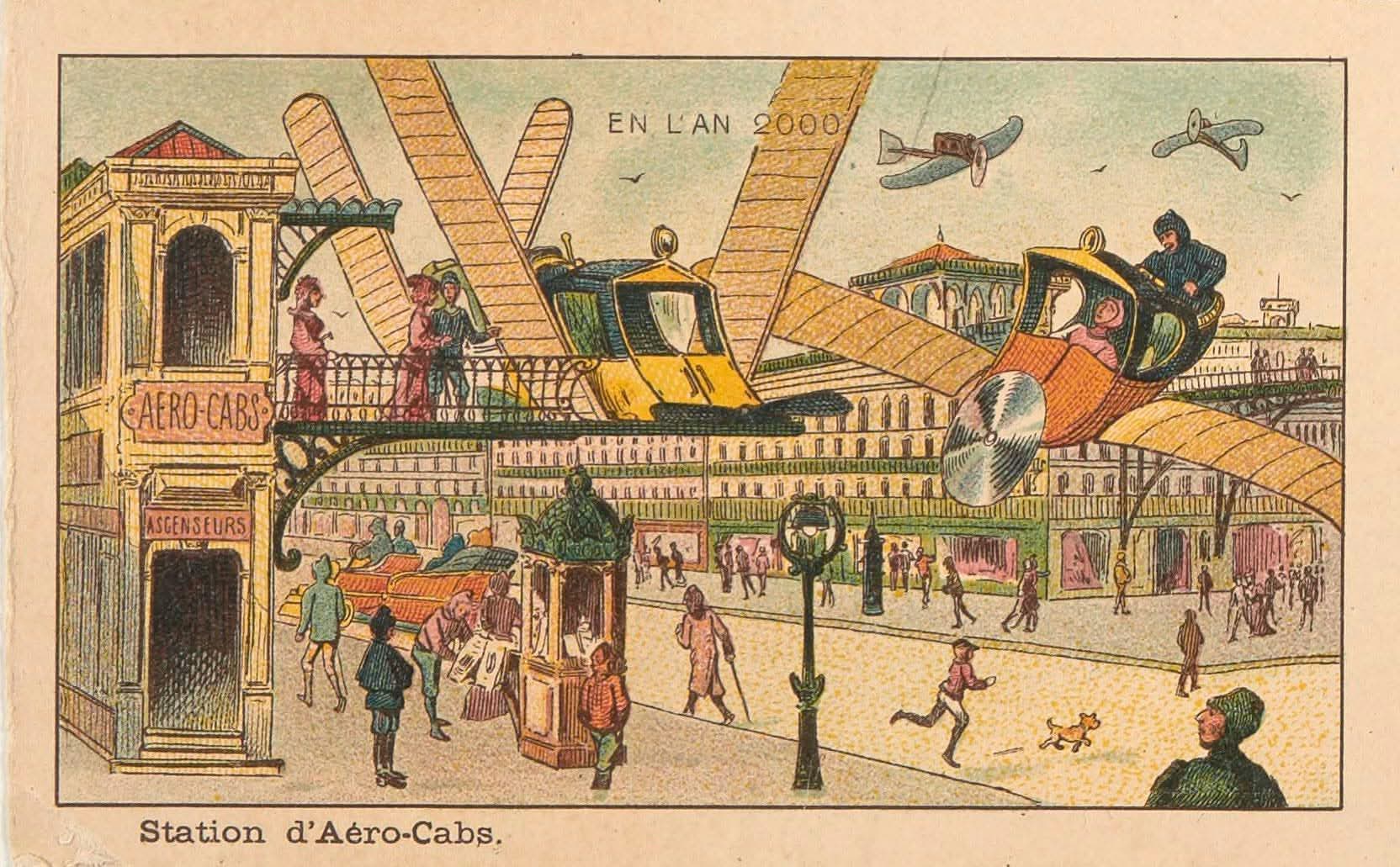

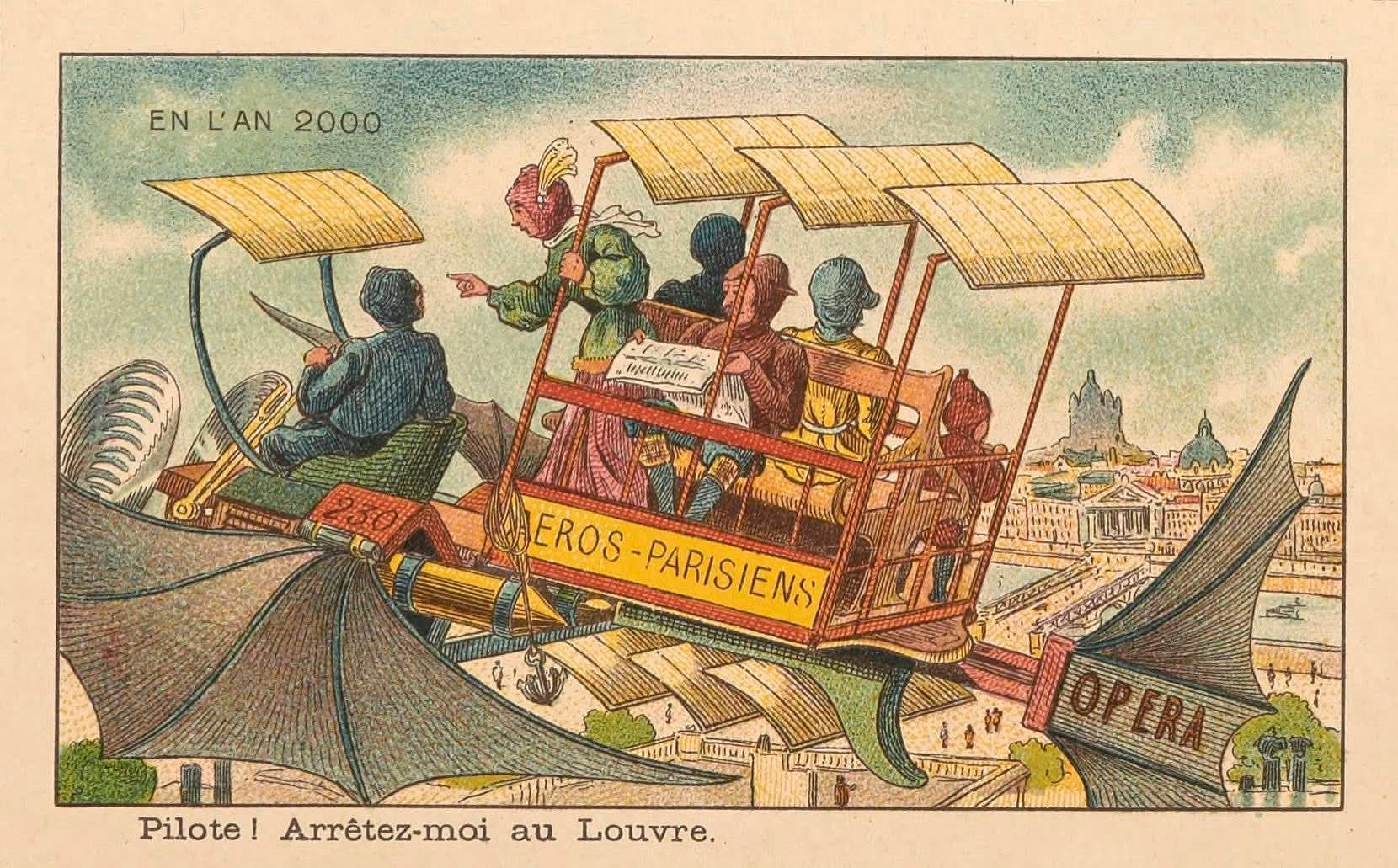

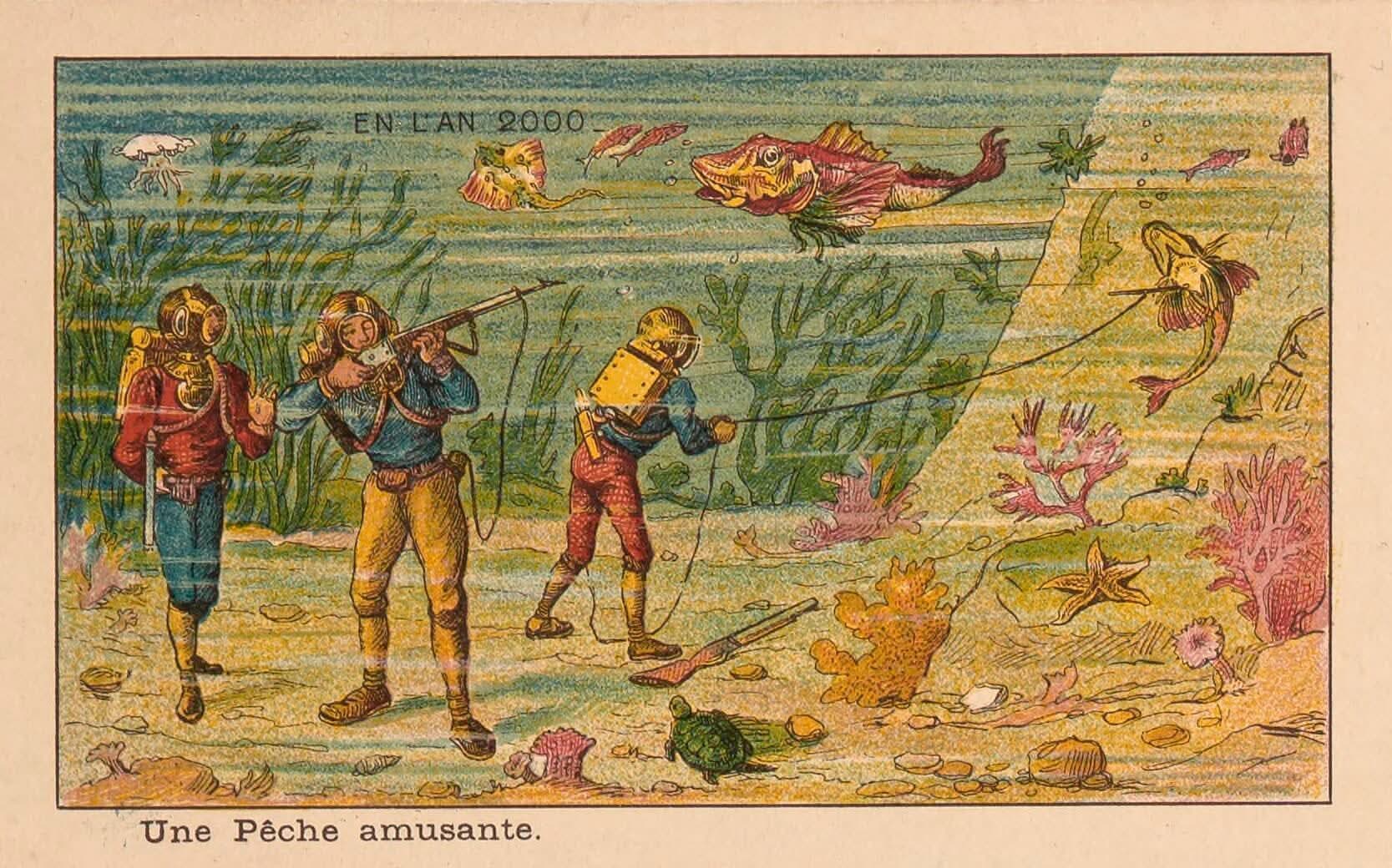

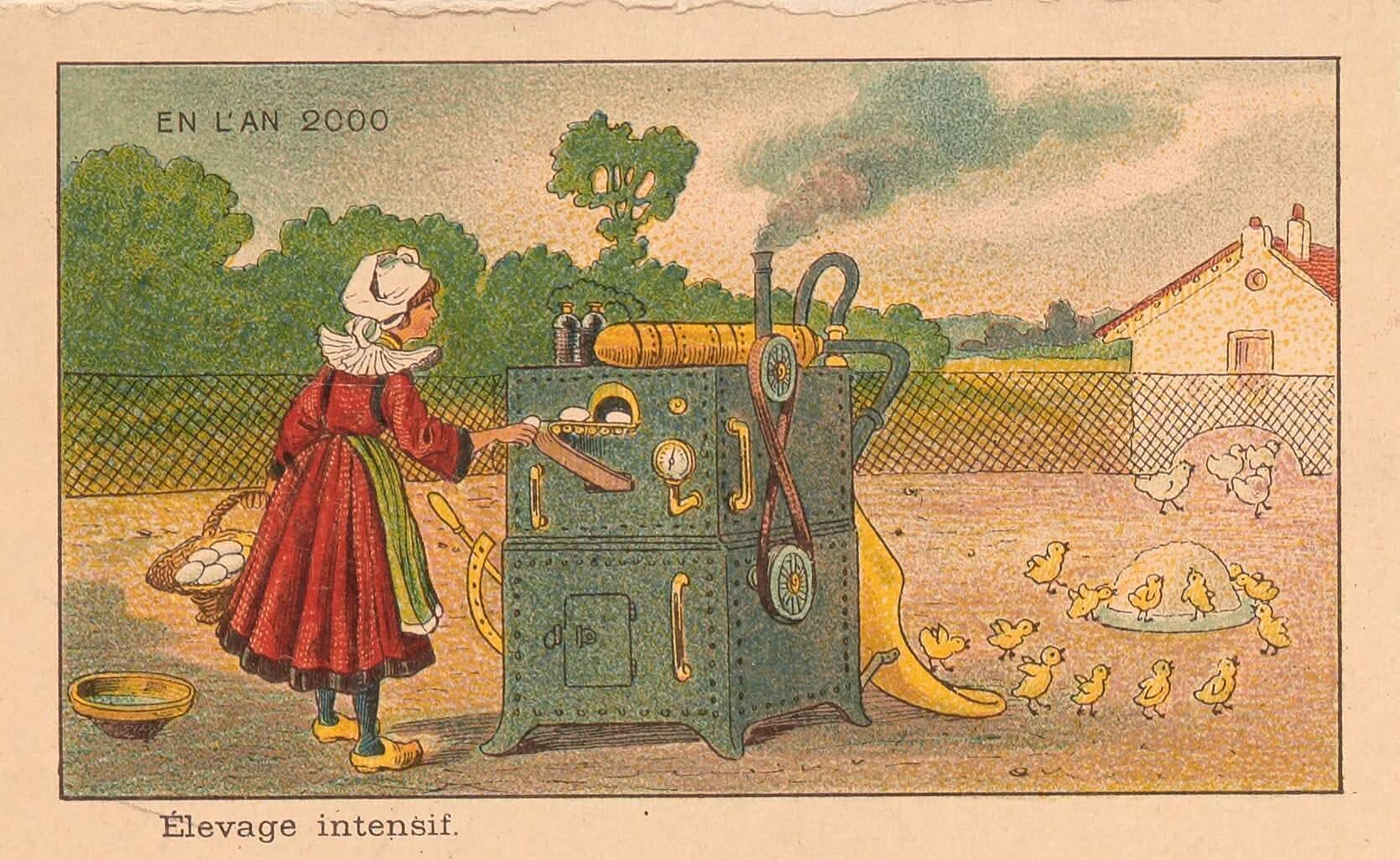

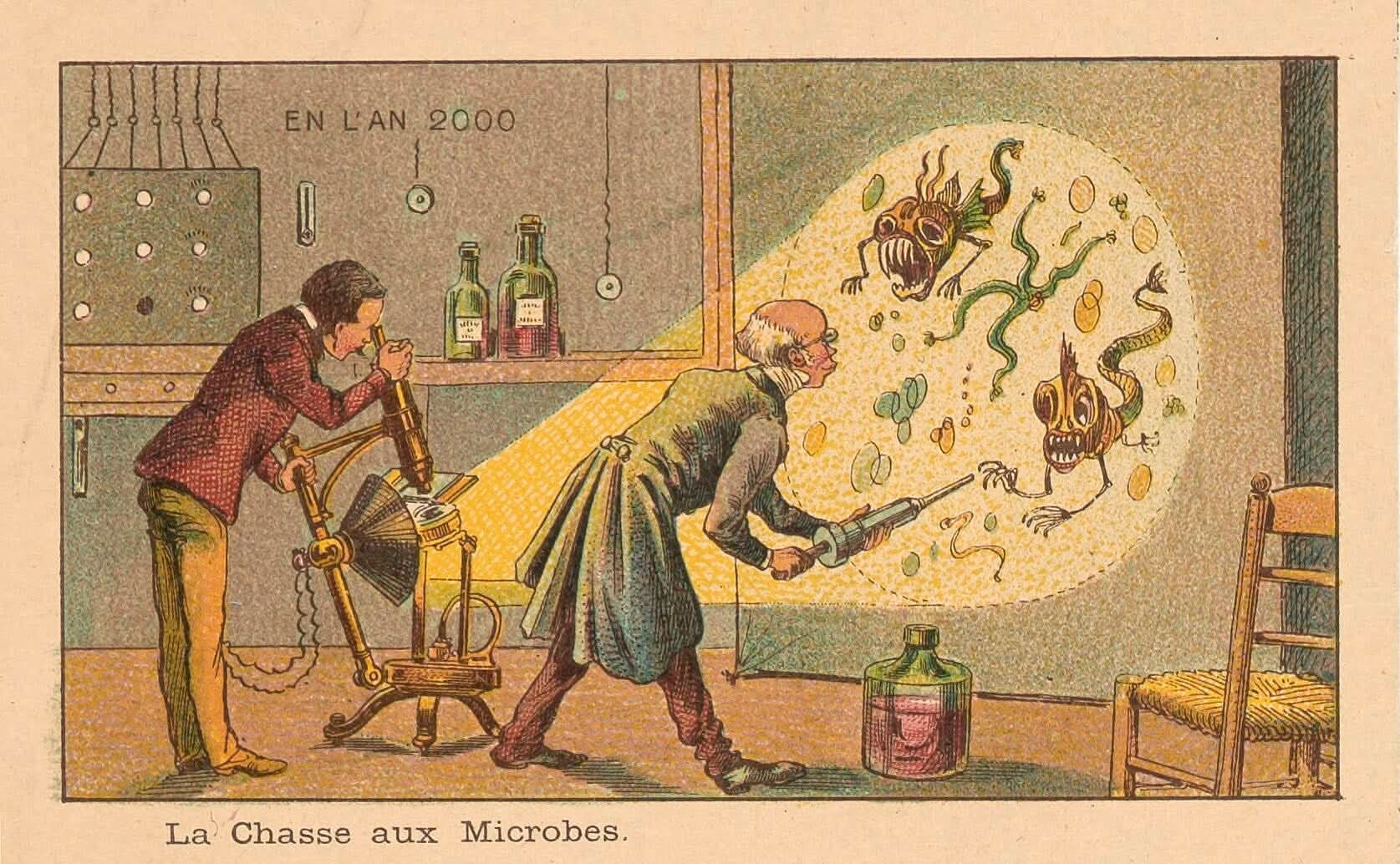

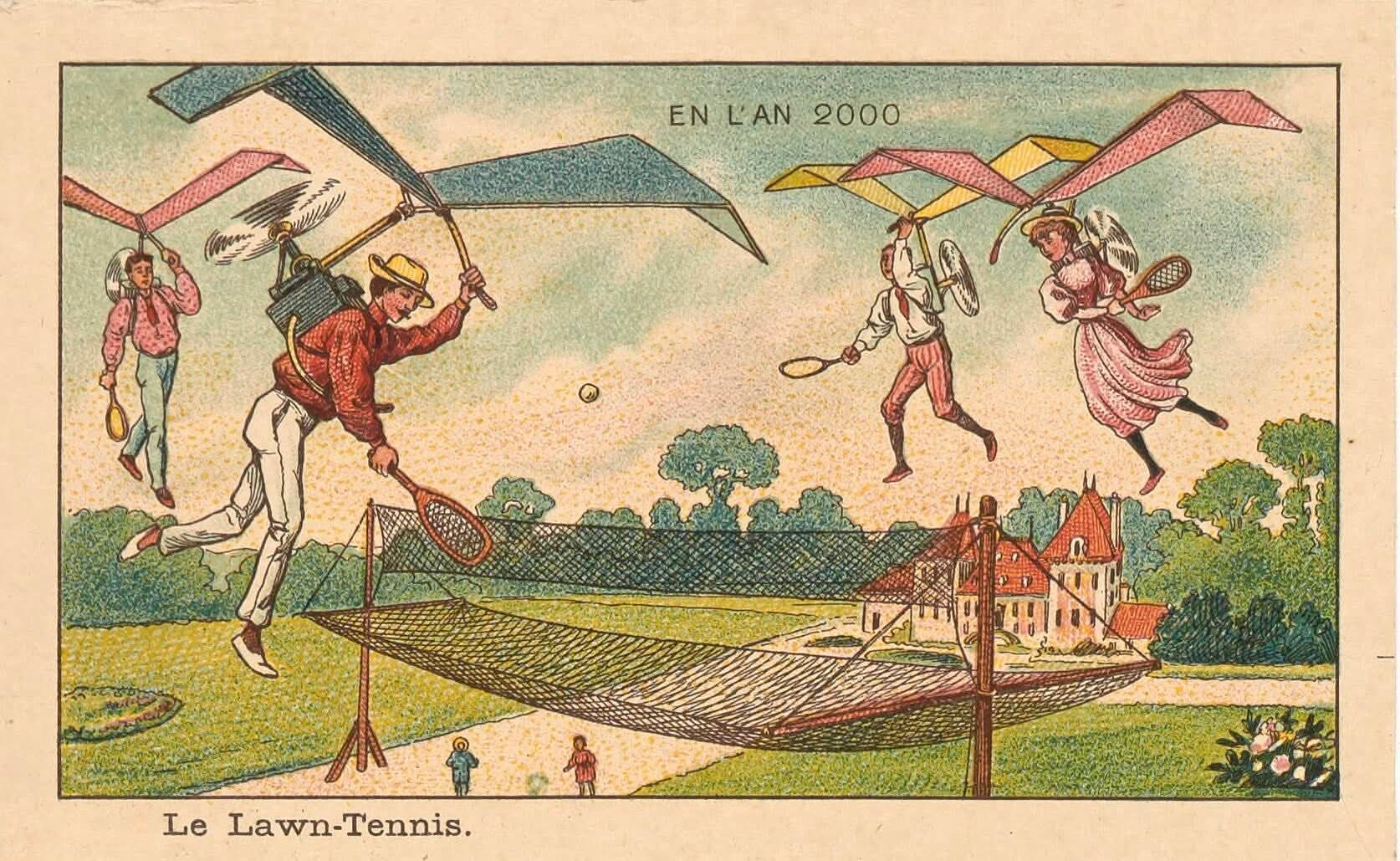

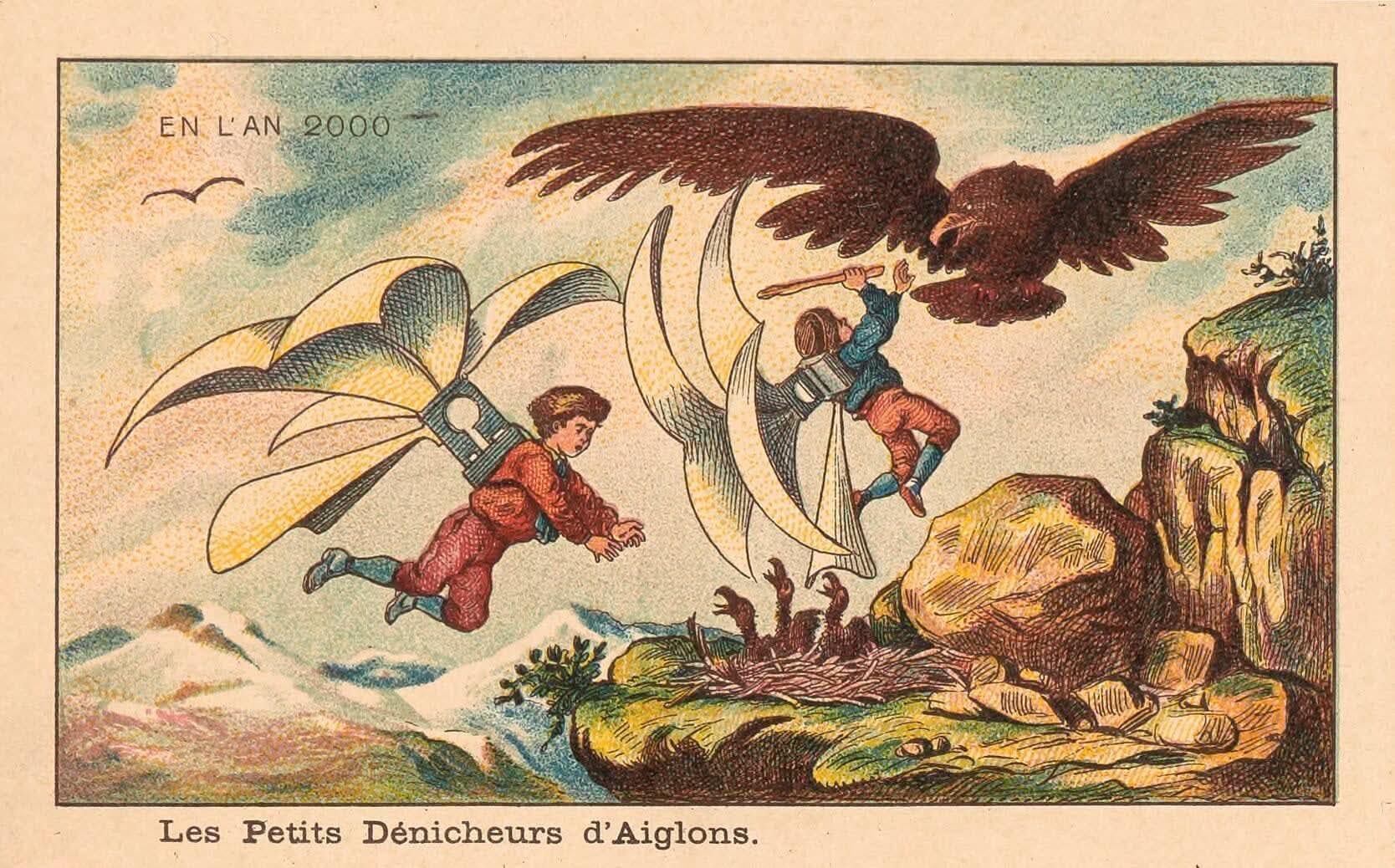

What did the year 2000 look like in 1900? Initially commissioned by Armand Gervais, a French toy manufacturer in Lyon, for the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, the first fifty of these paper cards were produced by Jean-Marc Côté, designed to be enclosed in cigarette boxes and, later, sent as postcards. Côté and other artists made all in all, at least seventy-eight cards, although the exact number is not known, and some may still remain undiscovered. Each tries to imagine what it would be like to live in the then-distant year of 2000.

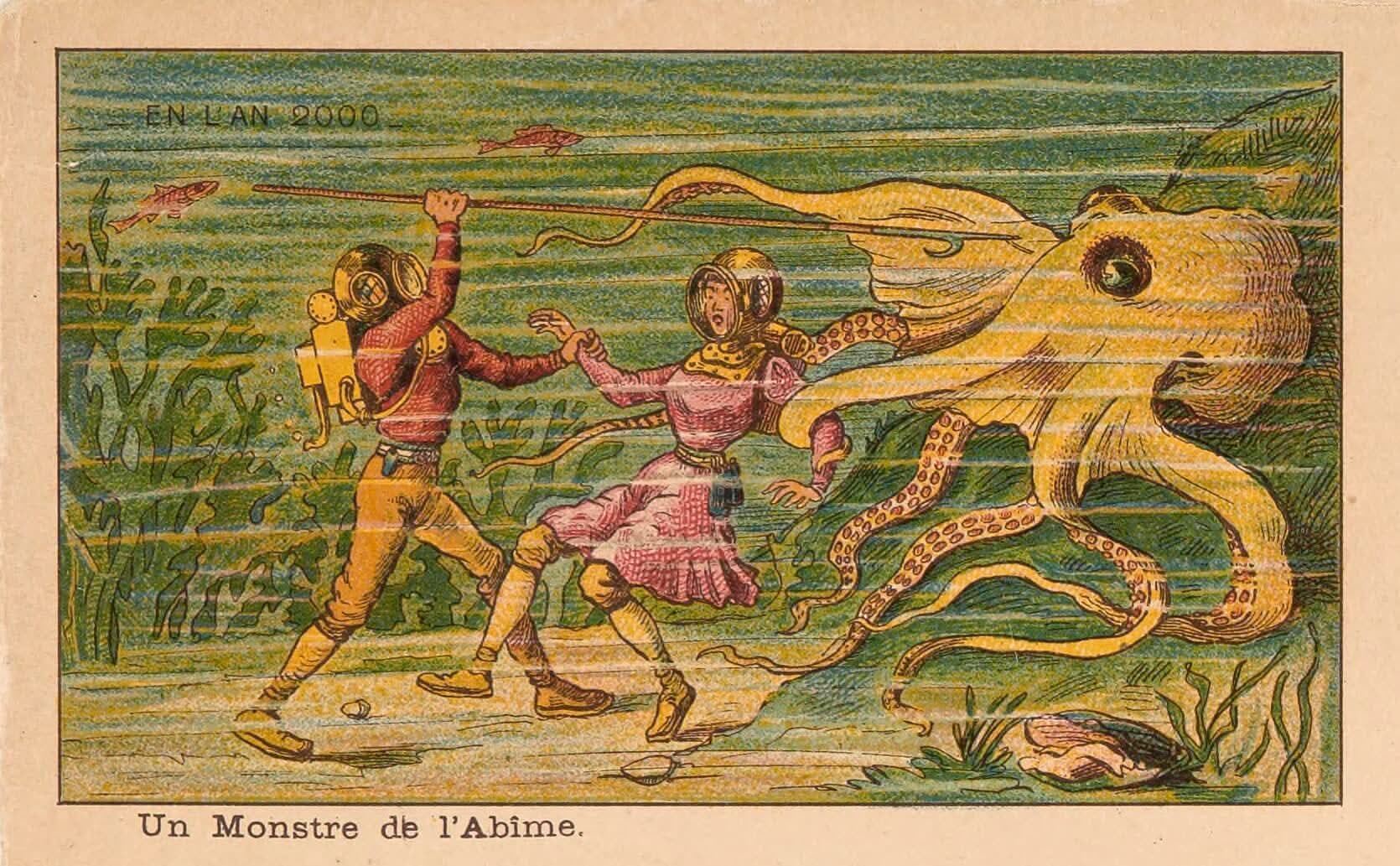

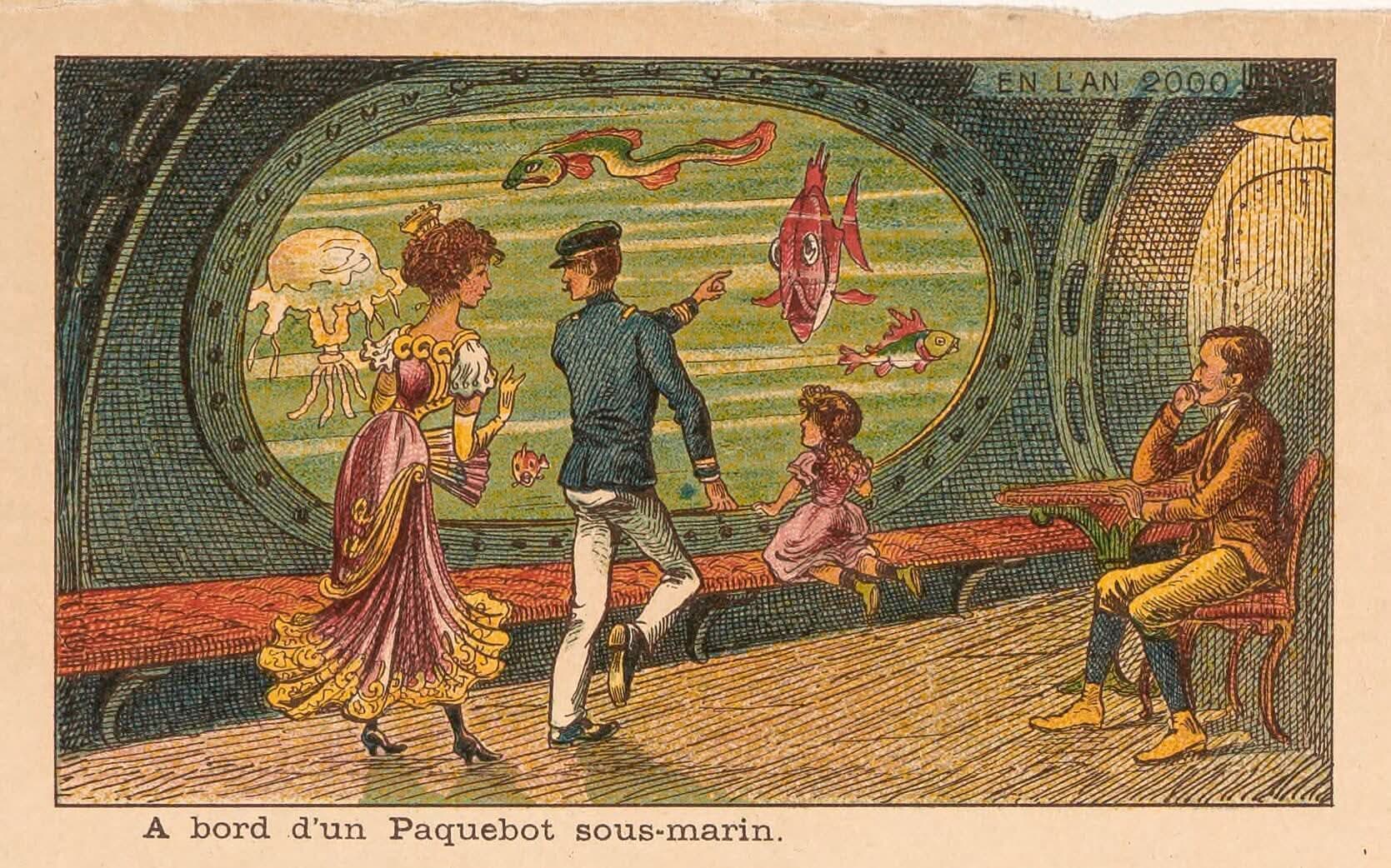

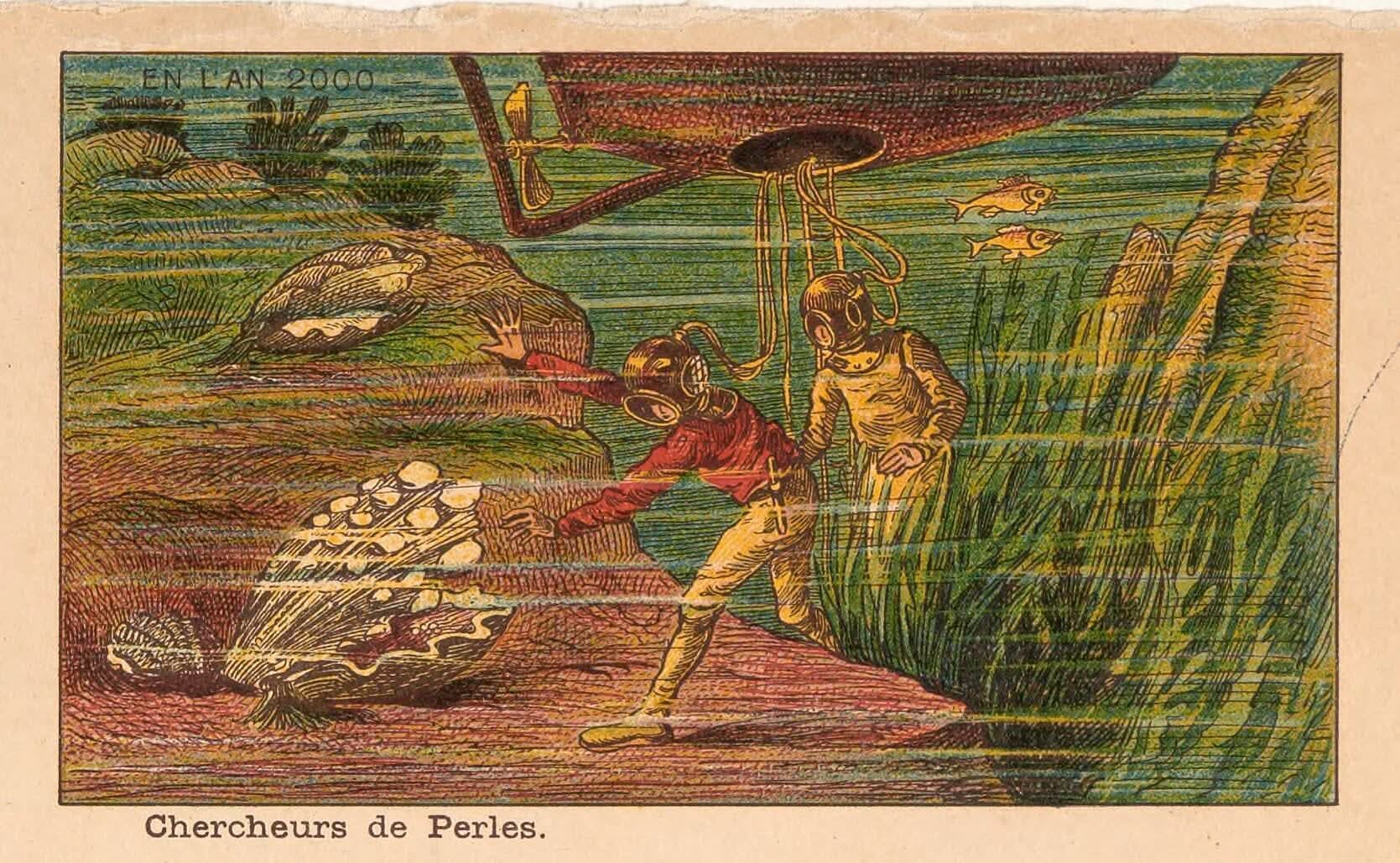

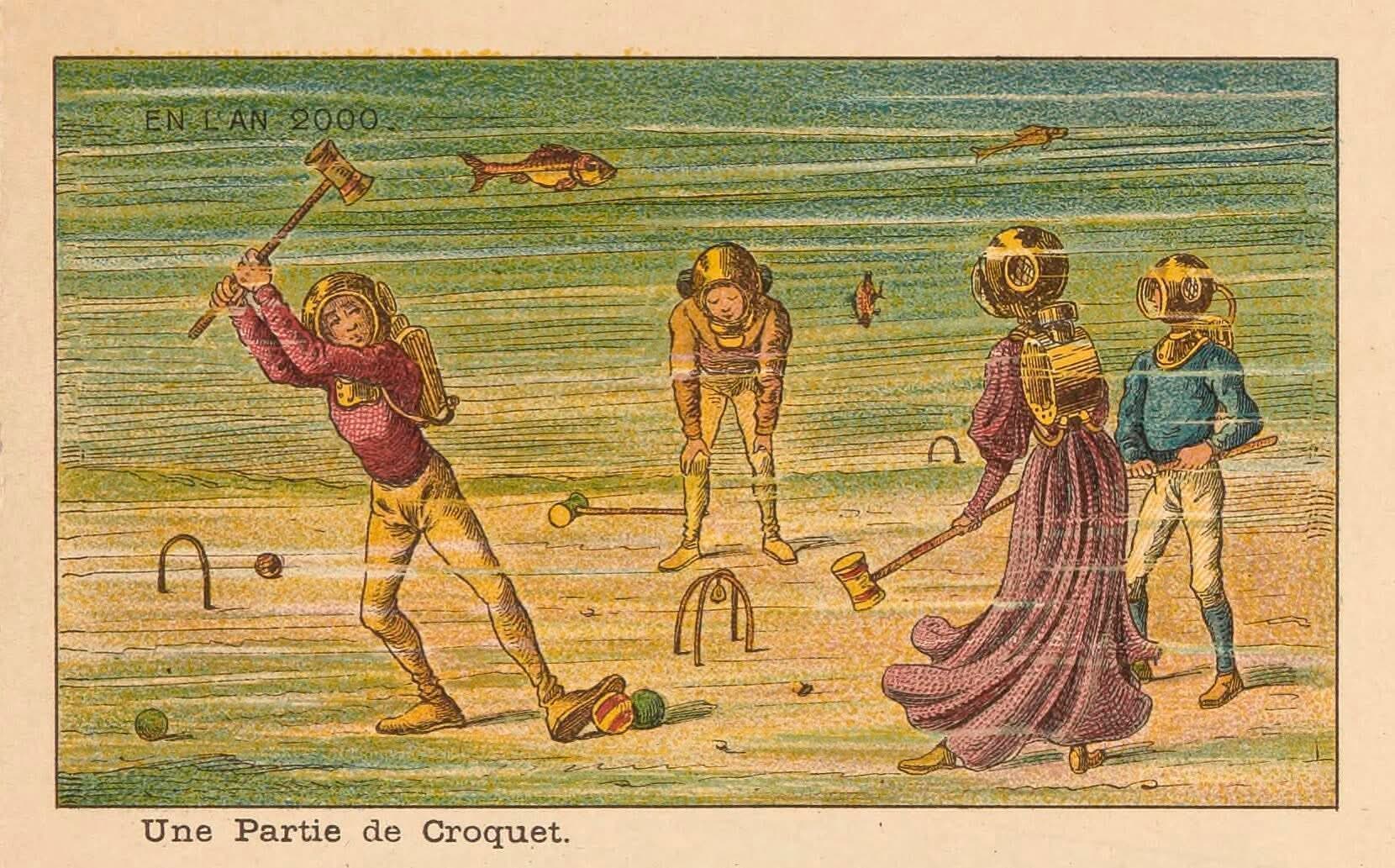

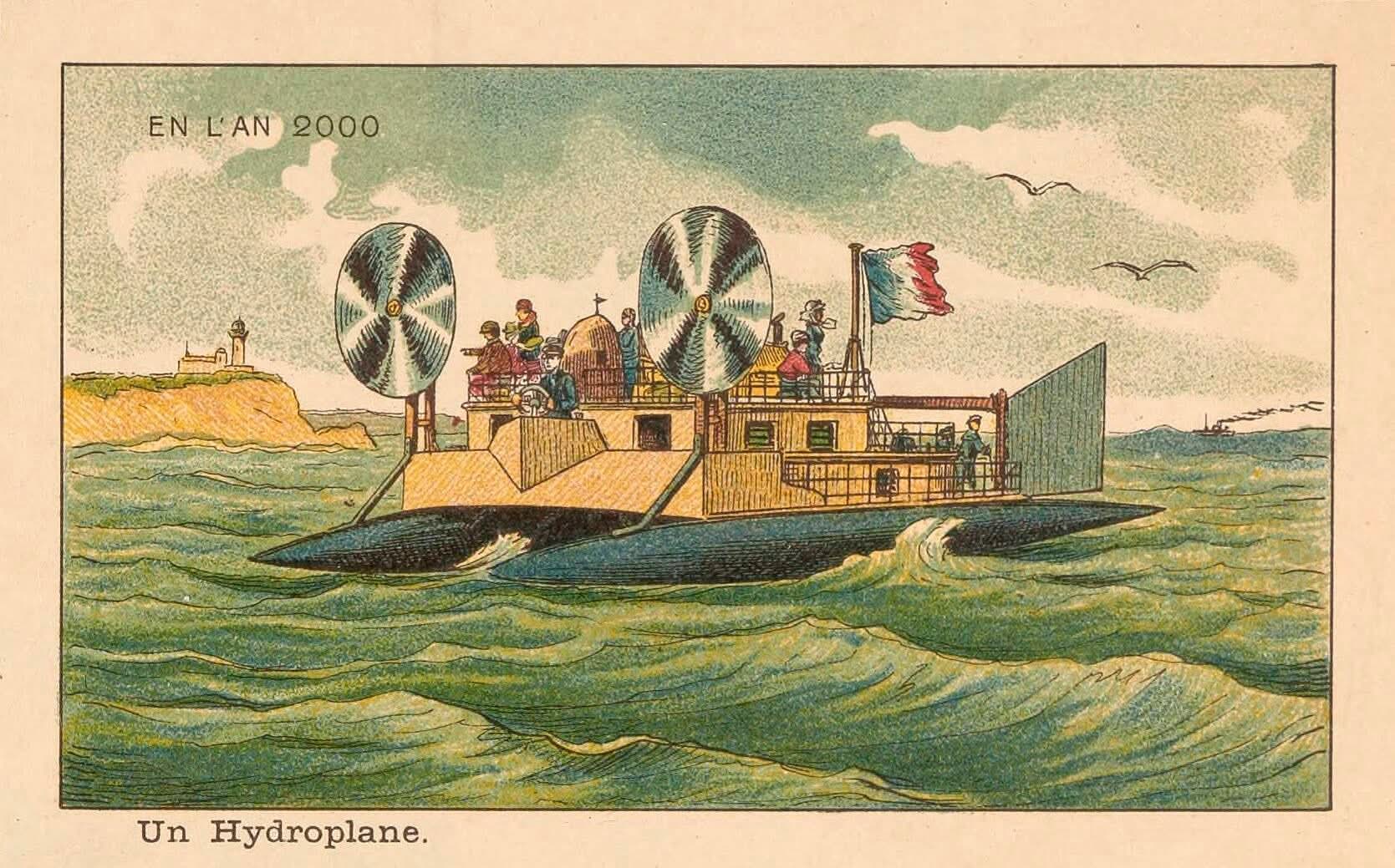

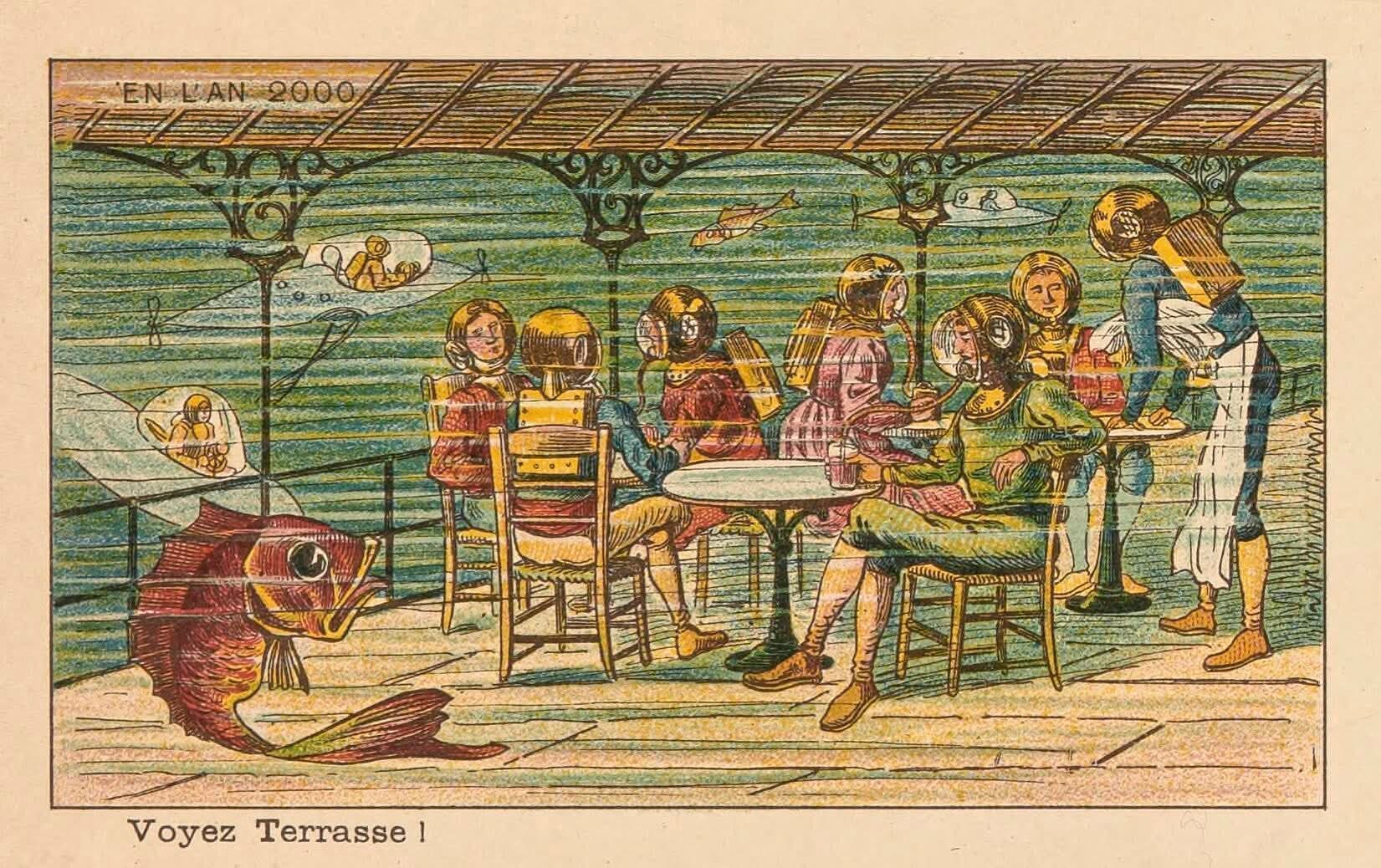

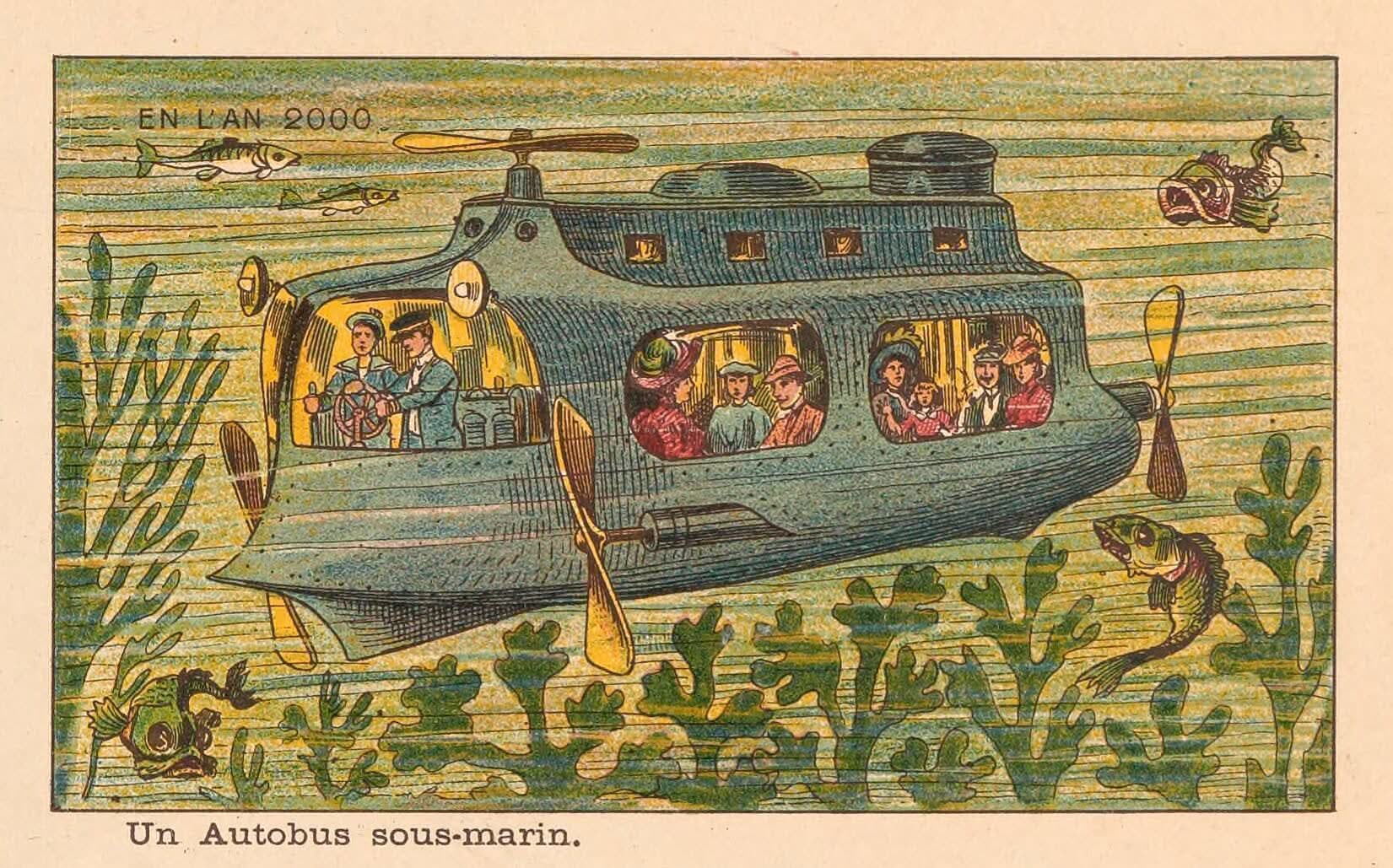

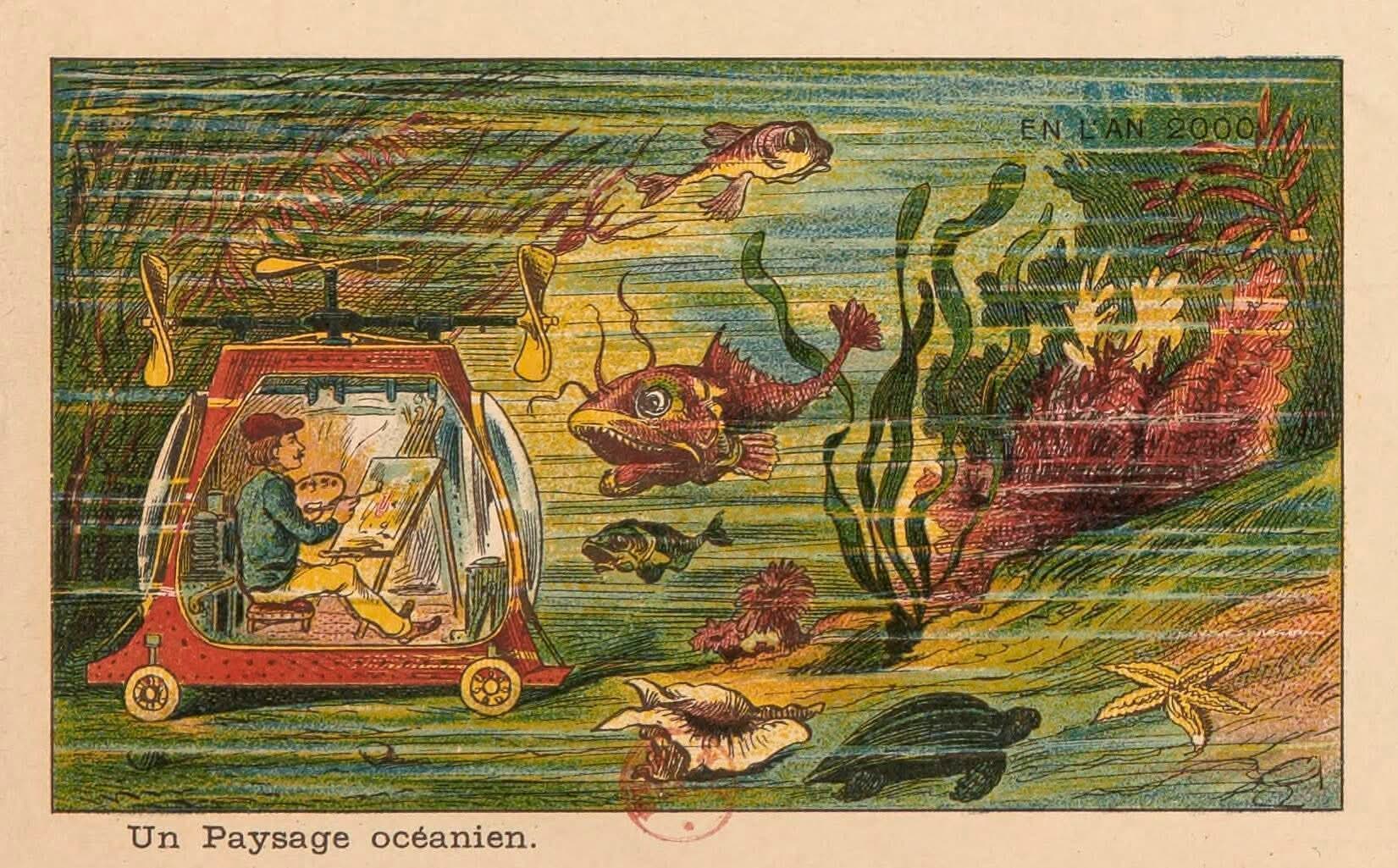

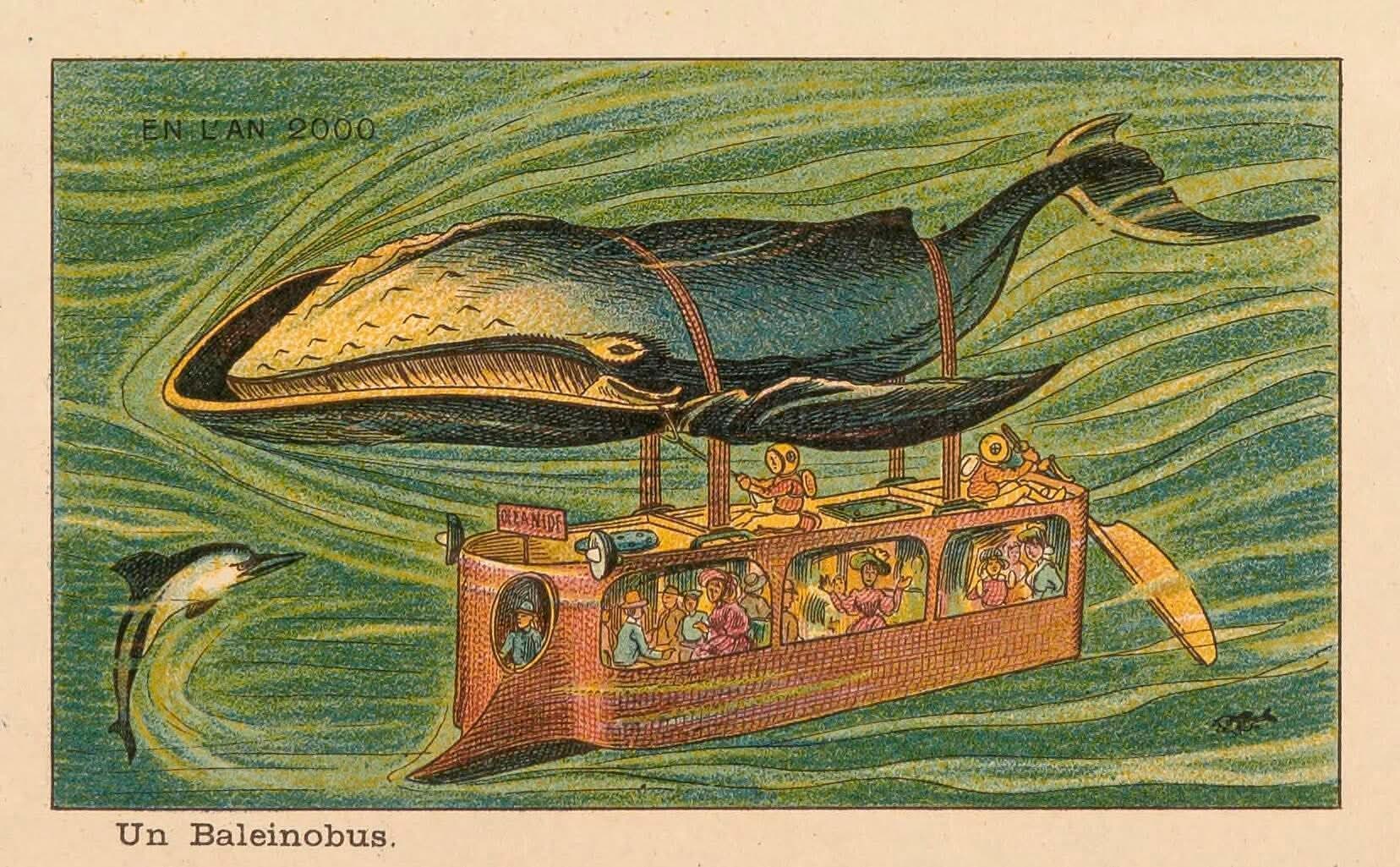

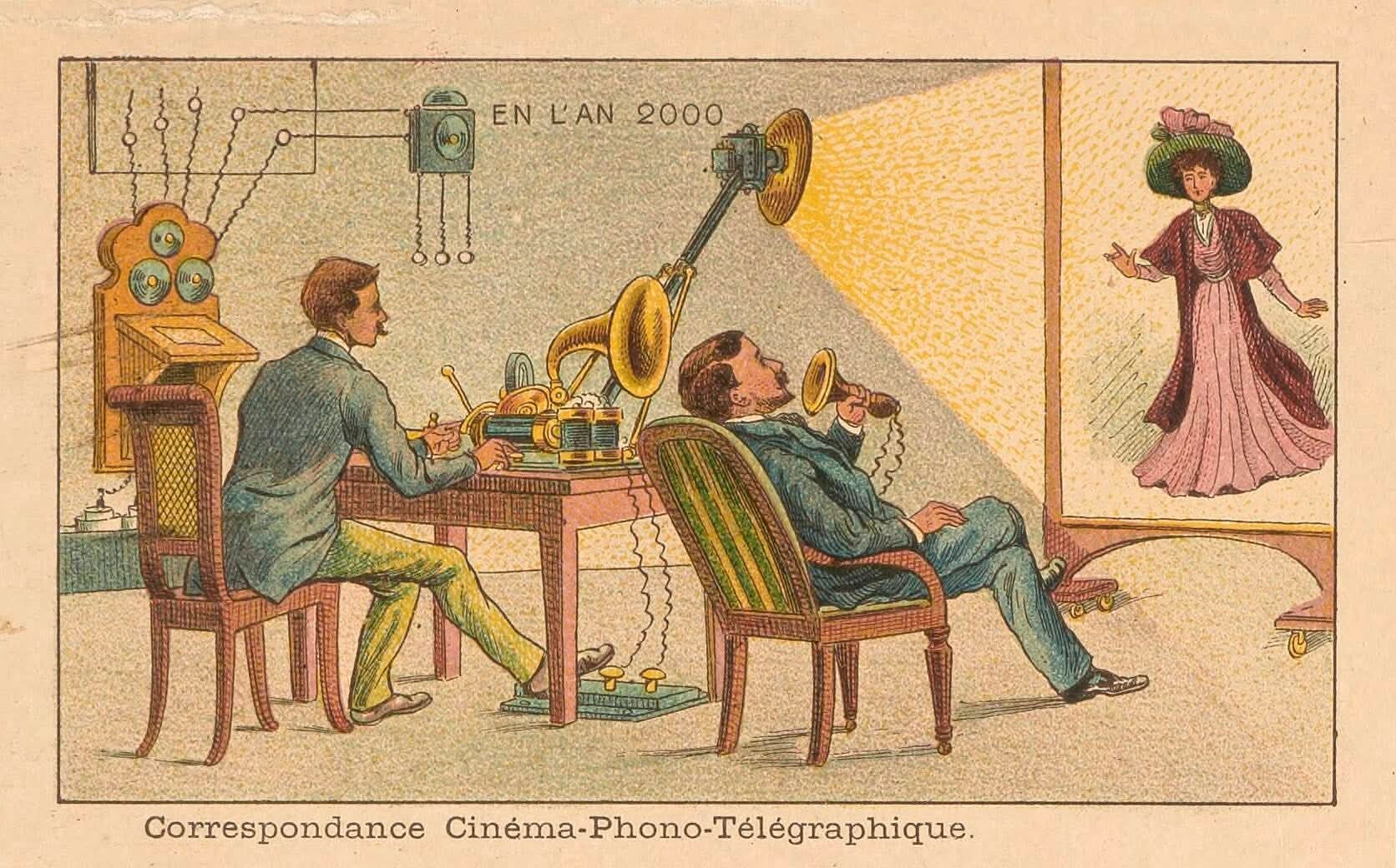

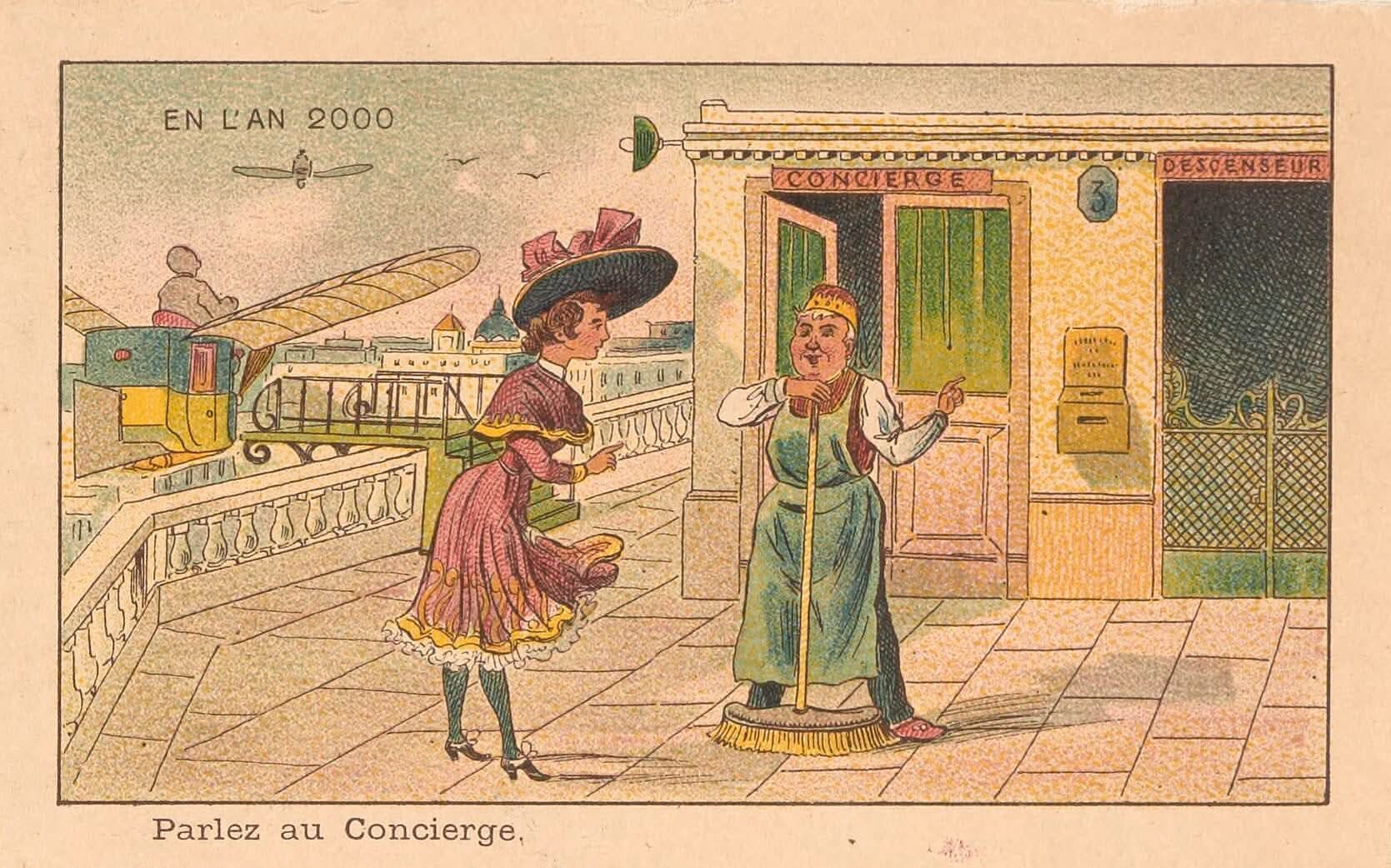

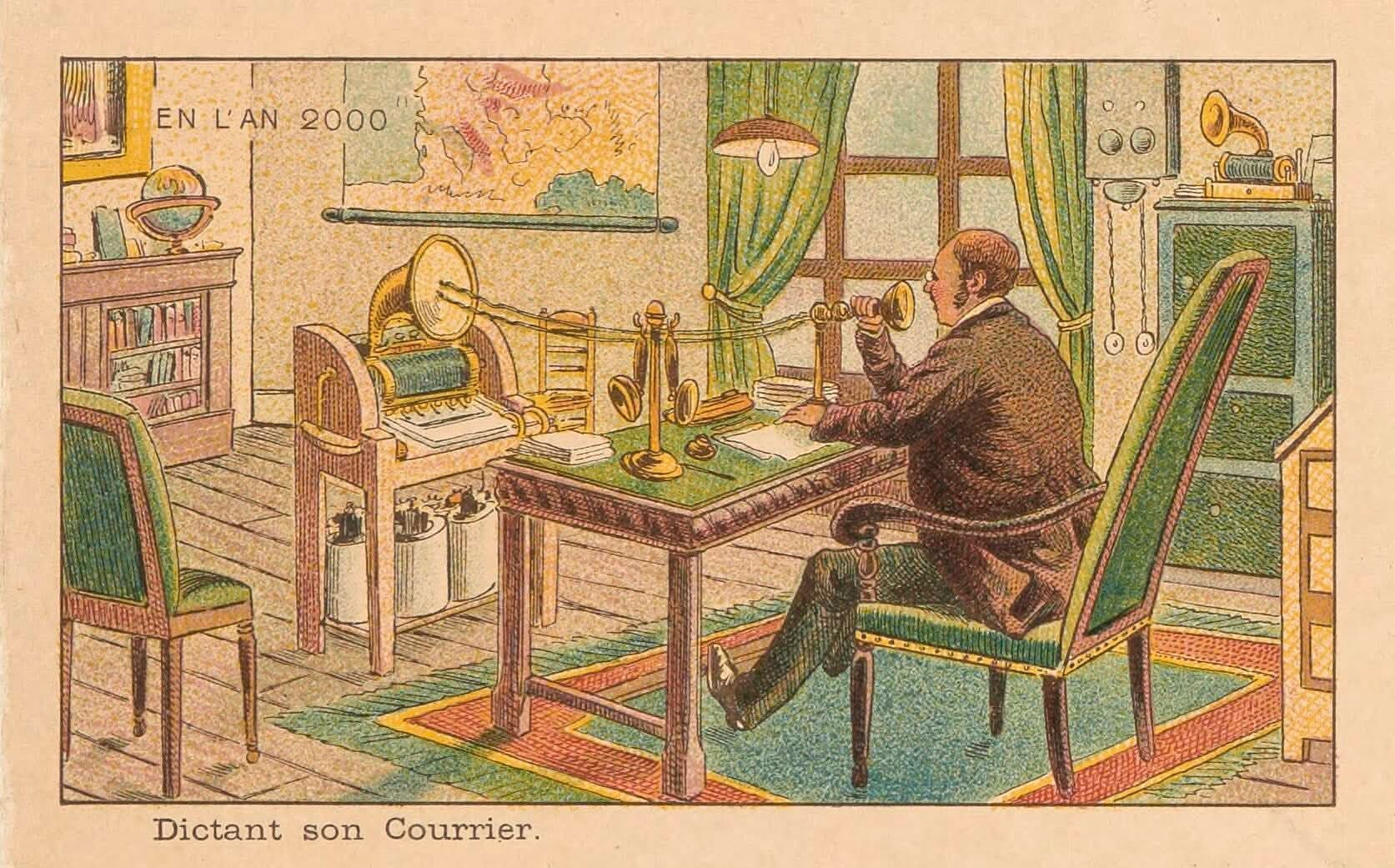

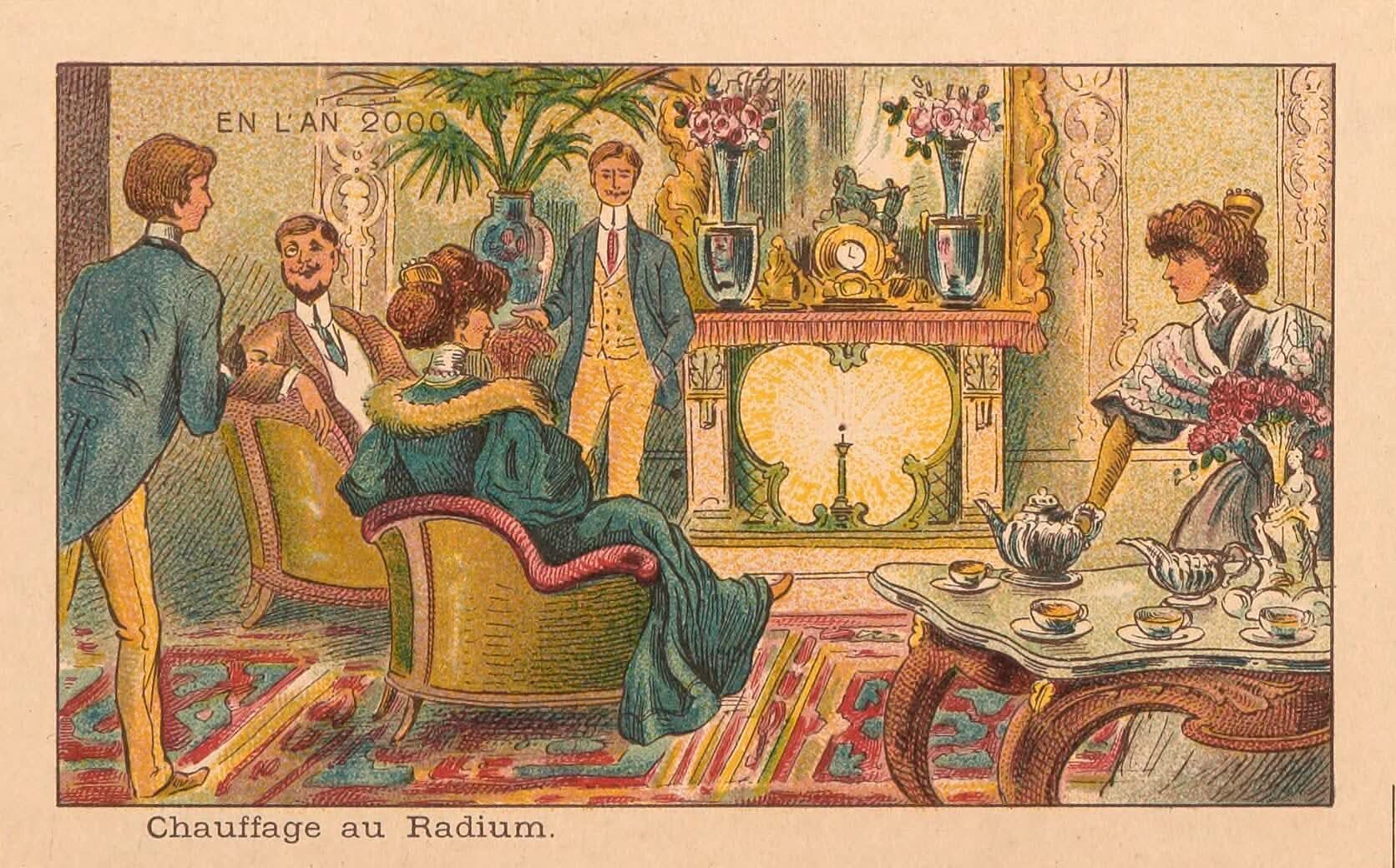

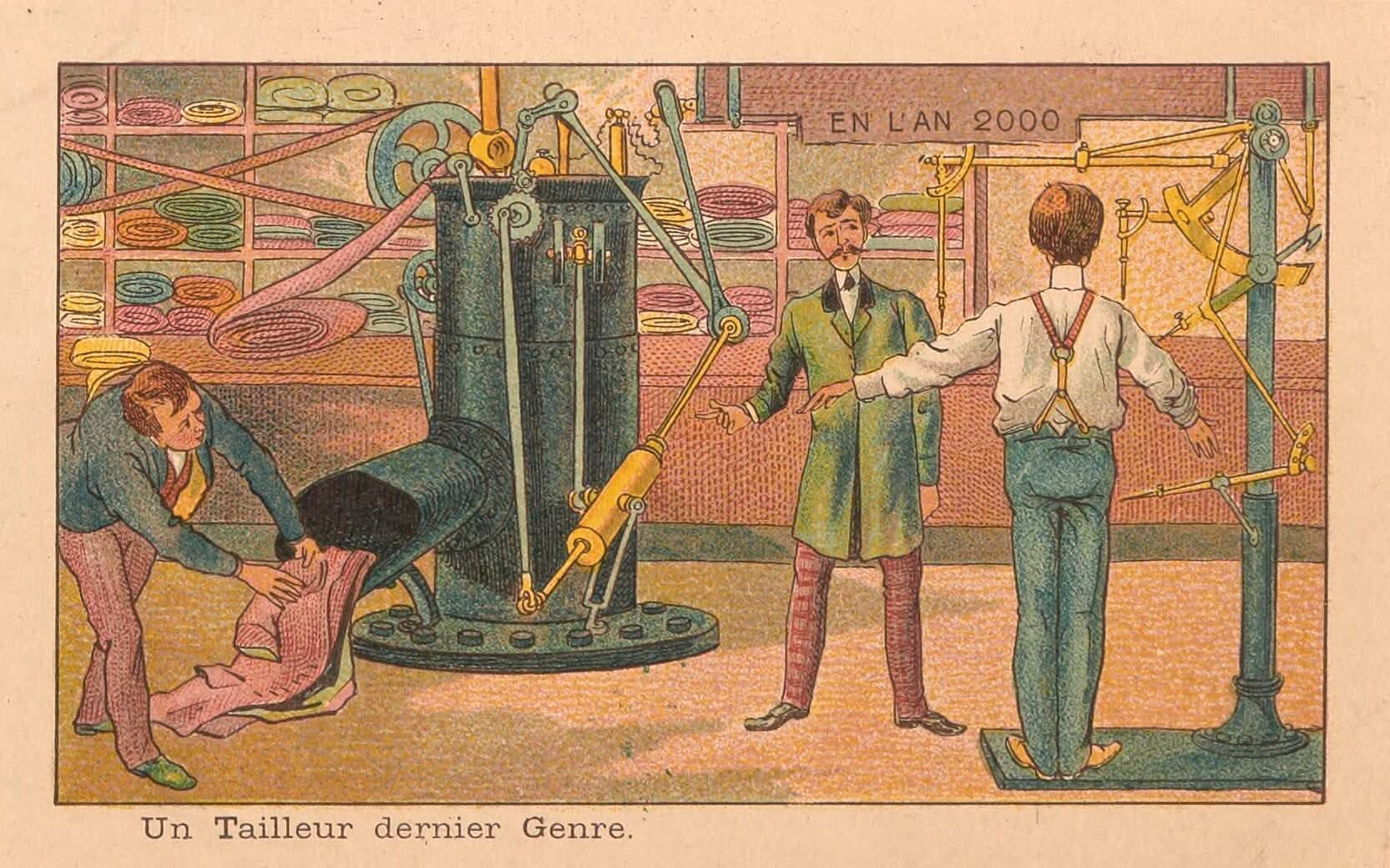

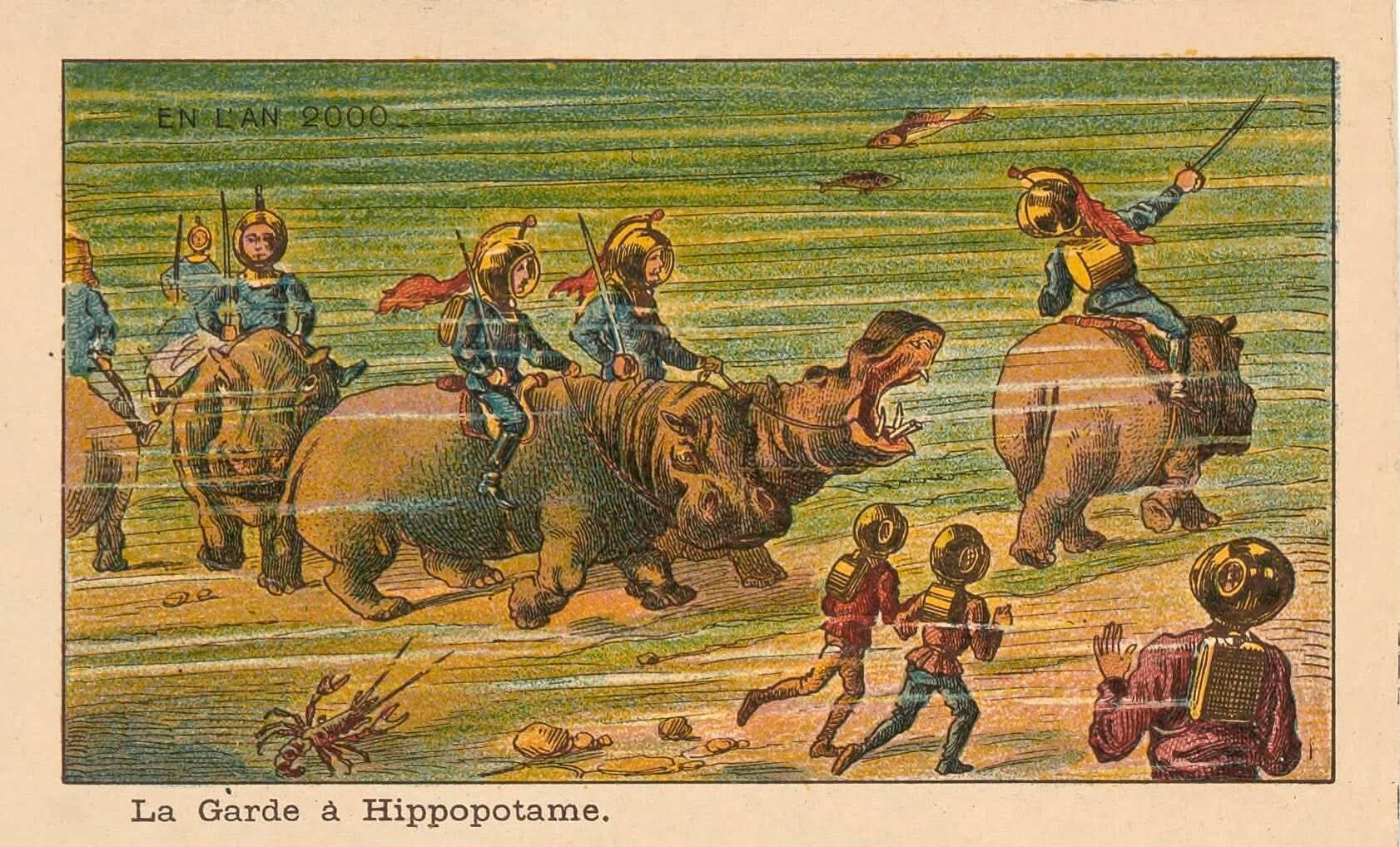

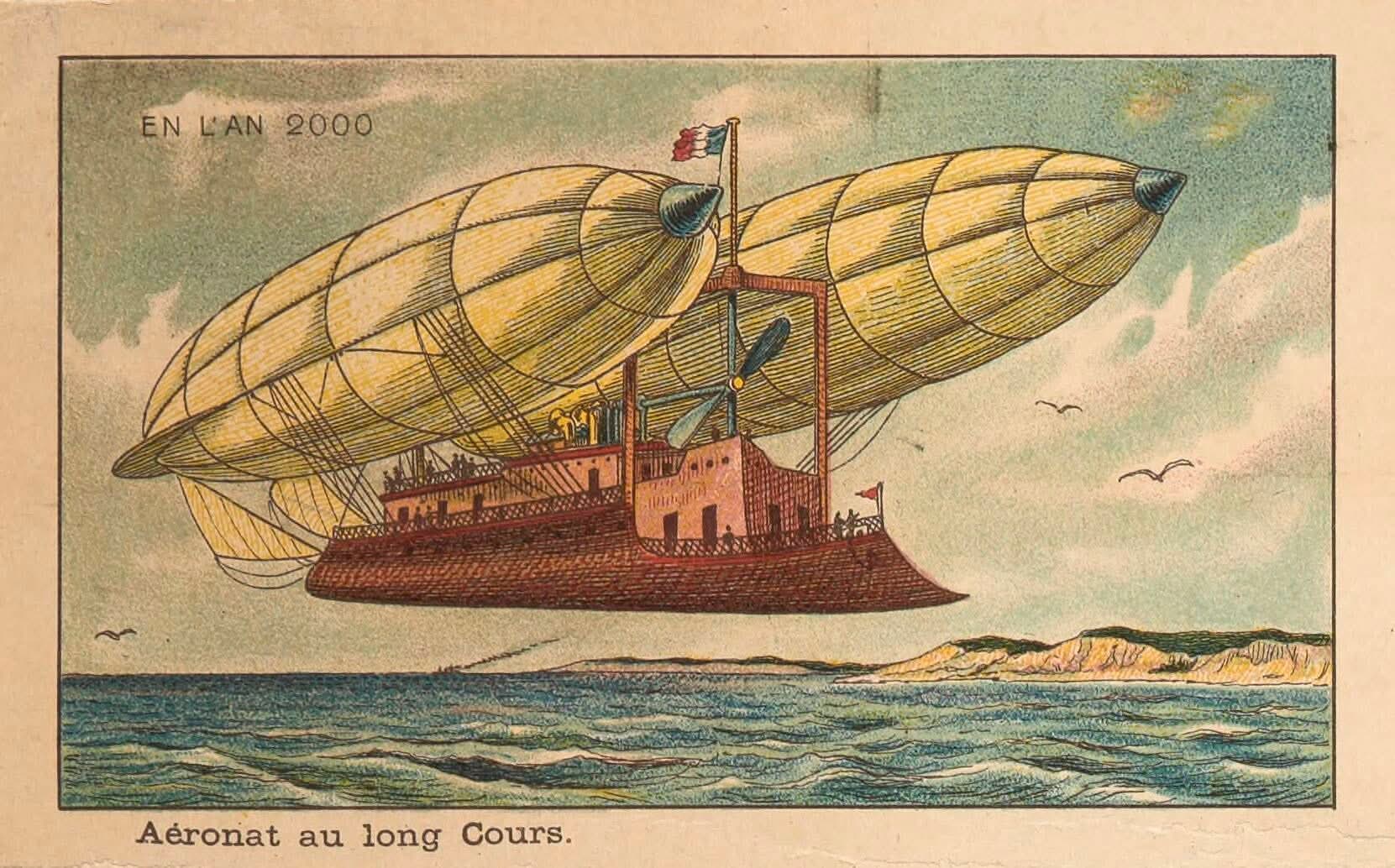

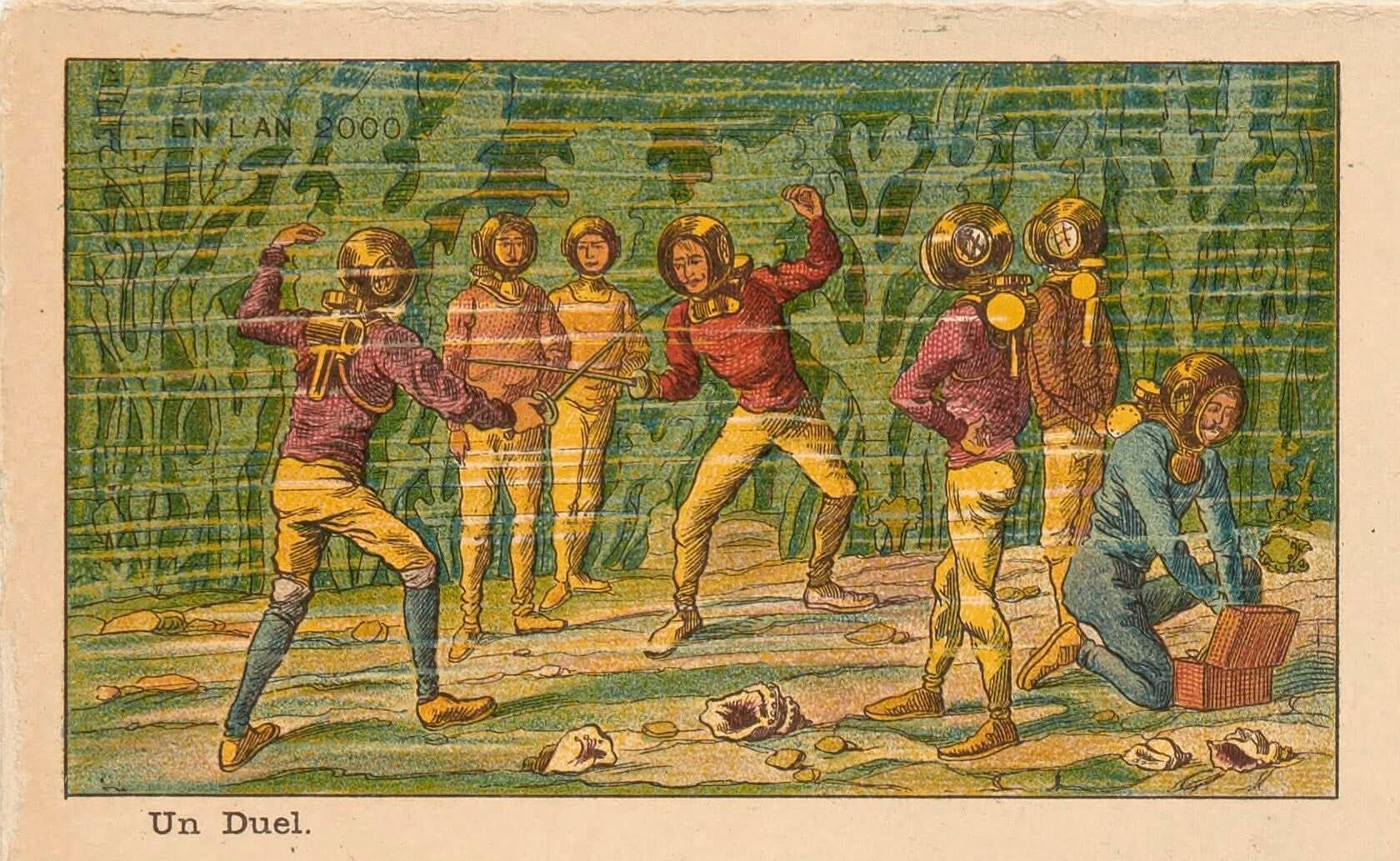

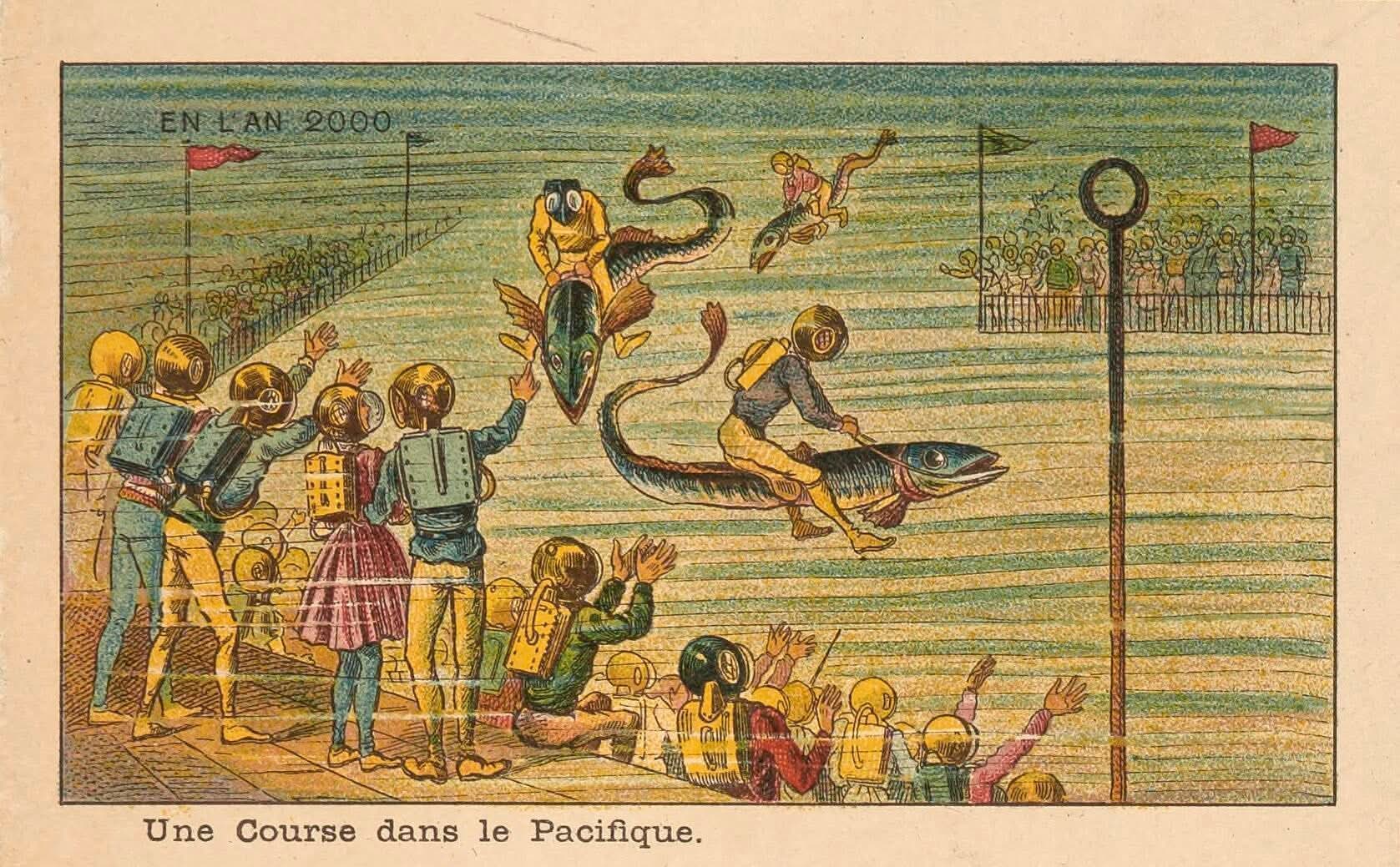

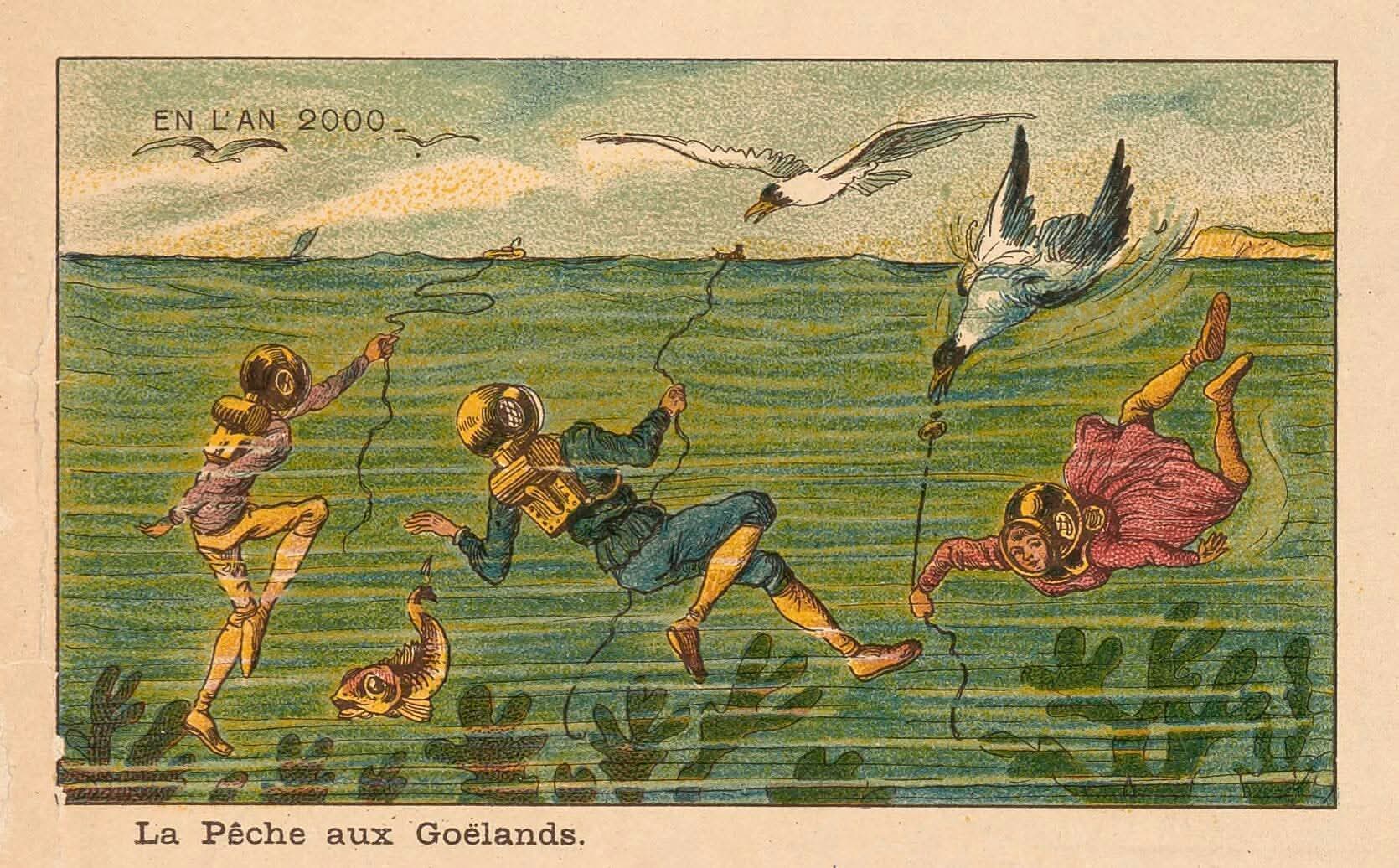

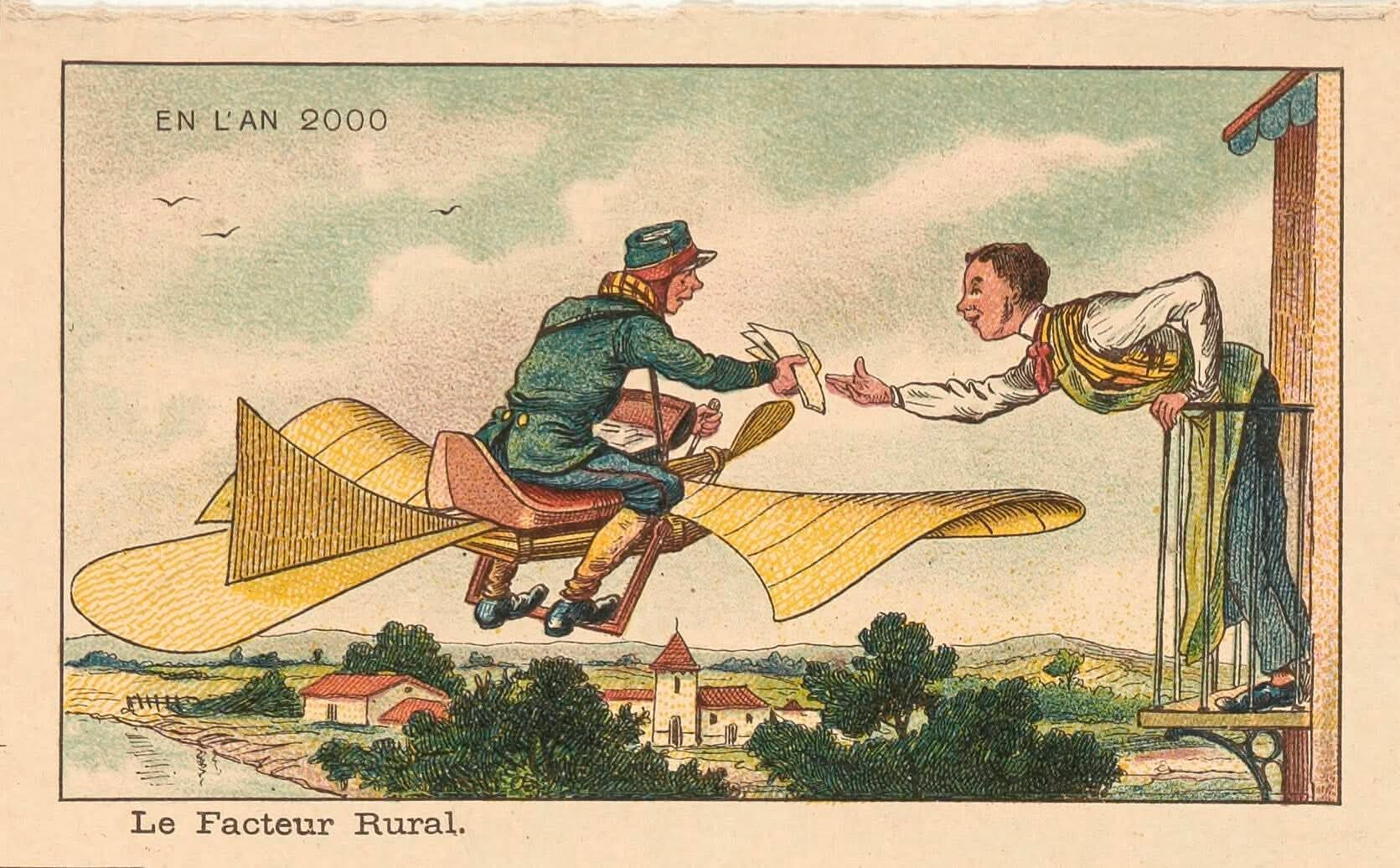

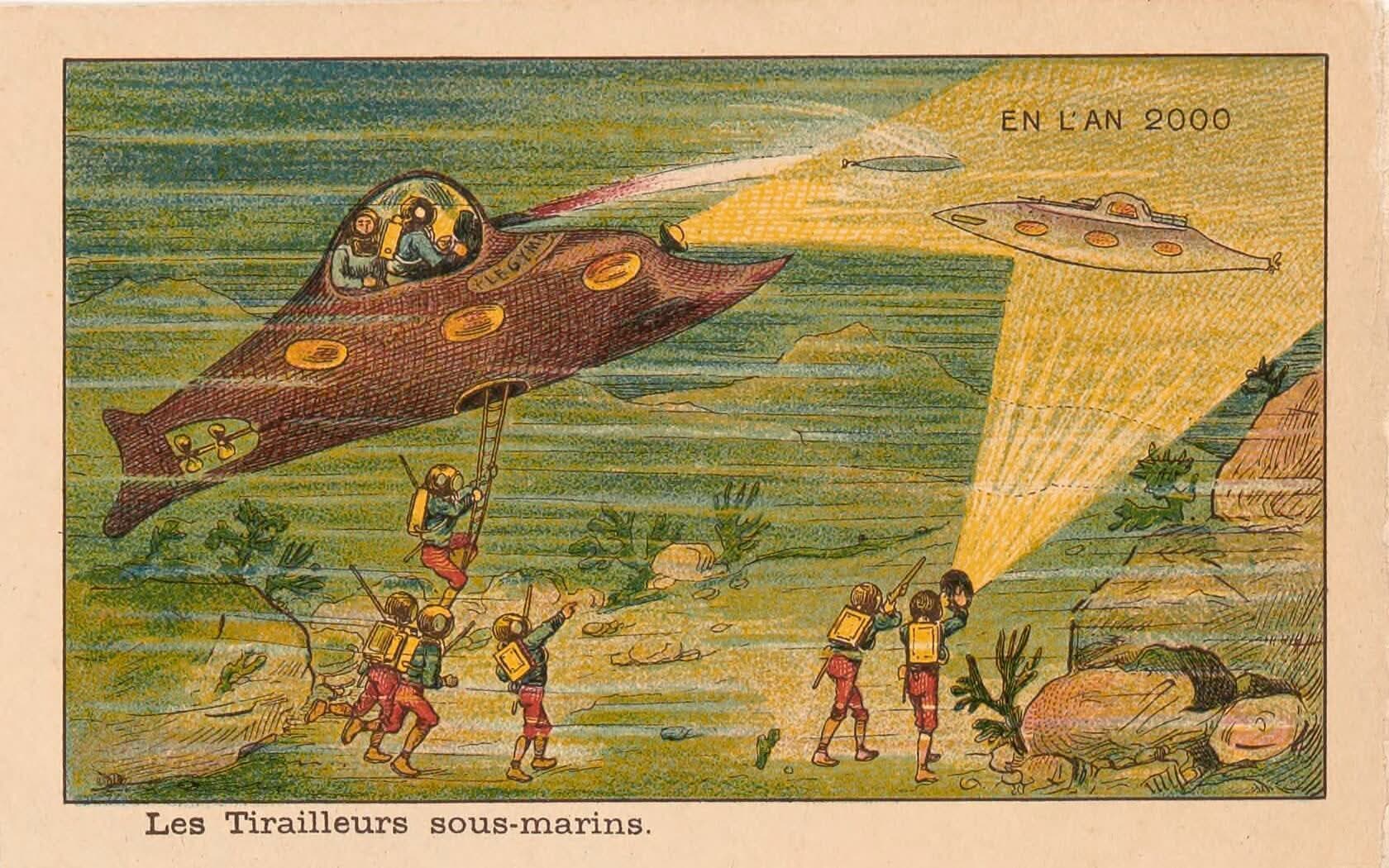

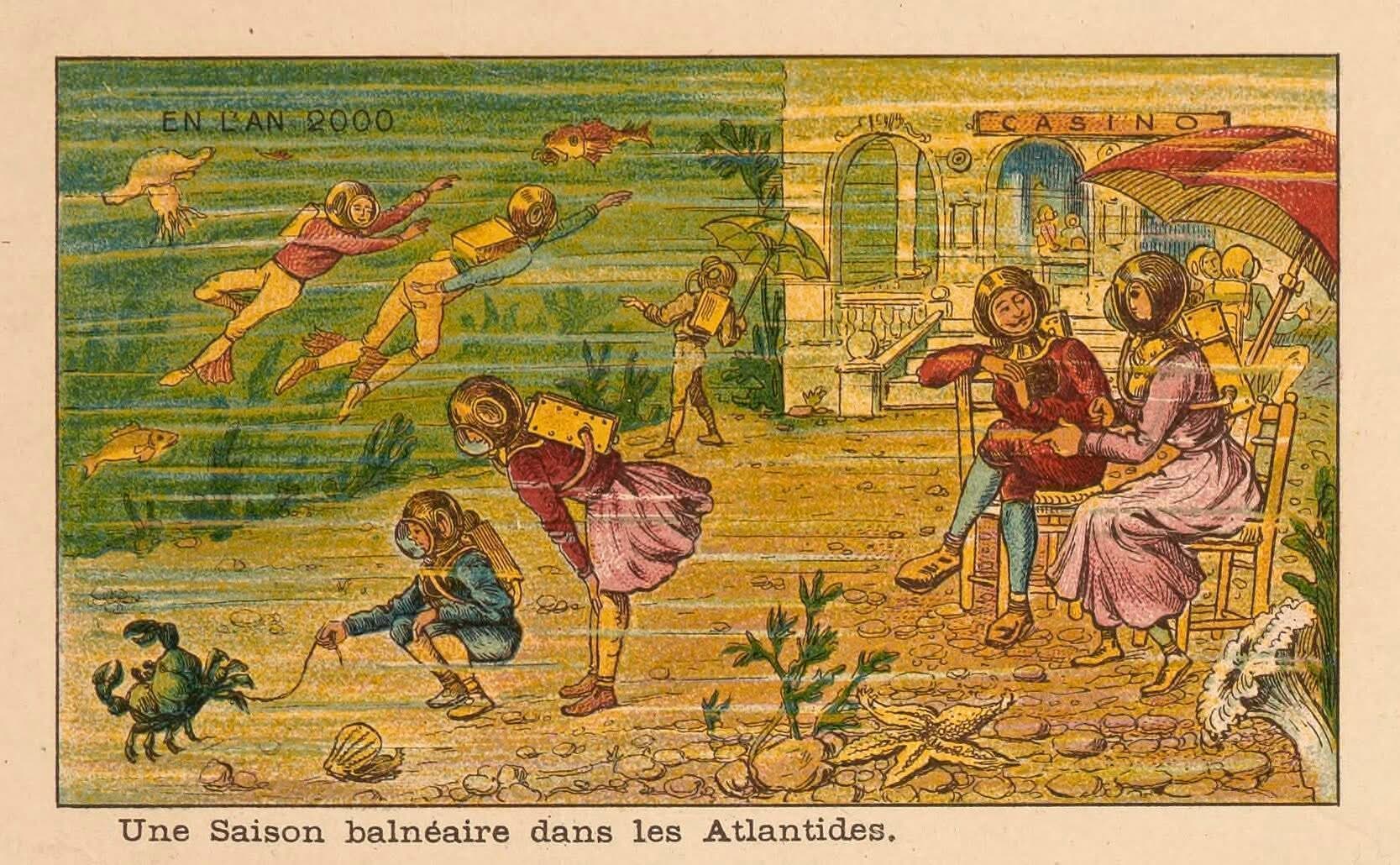

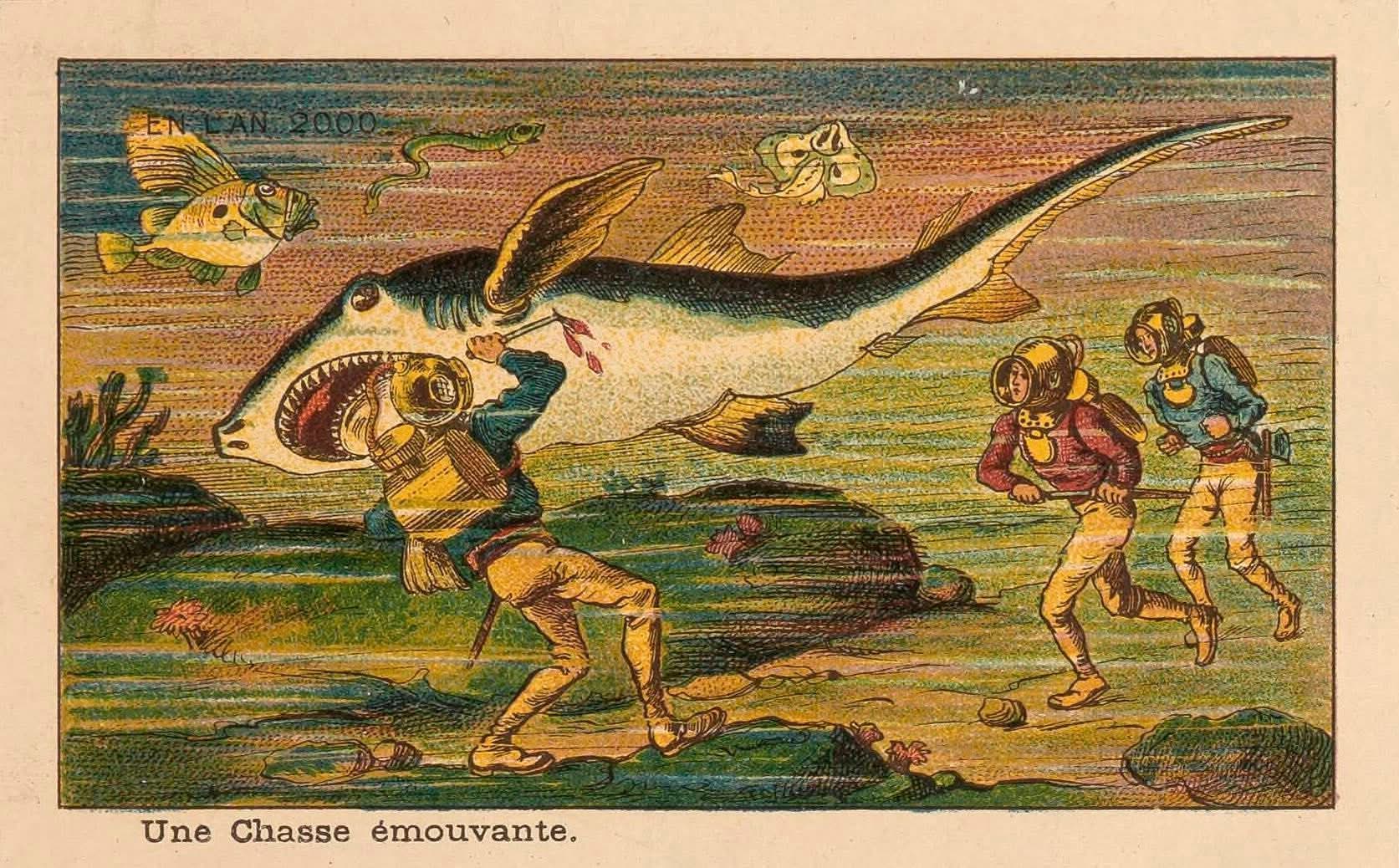

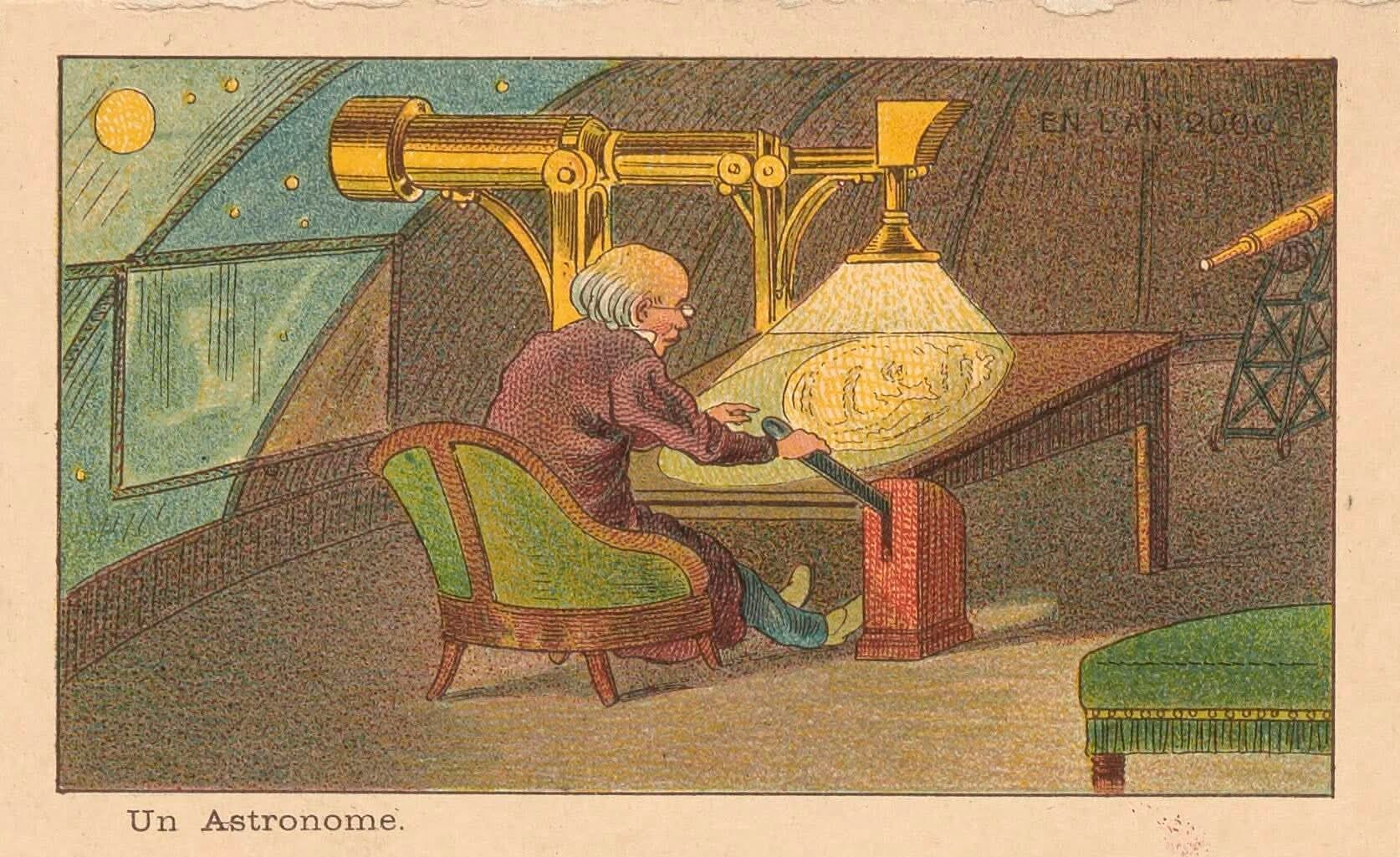

Some technologies are wonderfully prescient. Chicken eggs are incubated with machines. Tailoring is partially automated. Crowds assemble at the symphony for electronic music. The most accurate depictions are in the theaters of warfare and industrial agriculture -- testament to the driving economic forces of technological development across the twentieth century: gatling guns affixed to automobiles, blimp-like battleships, fields cut with combine harvesters. As is so often the case, other predictions fall some way off the mark, failing to go far enough in thinking outside the confines of their current technological milieu (hence the ubiquity of propellers, a radium fireplace, not to mention the distinctly nineteenth-century dress). Still other predictions remain bizarre, mainly those that anticipated rapid nautical conquest: submarine divers trawling the sea's surface for seagulls, underwater croquet, a whale bus (exactly as it sounds).

These somewhat prescient scenes did not see the light of day until their future was nearly at hand. A few sets of cards were printed by Gervais in 1899 but he died during production. For the next quarter century, the cards sat idle in his defunct toy plant -- future visions shelved in a basement like forgotten relics from the past. An antiquarian bought the archive, transferring it to his own crypt for fifty more years, until the Canadian writer Christopher Hyde stumbled across them at his Parisian shop. Hyde in turn lent the cards to science-fiction author Isaac Asimov, who republished them in 1986, with accompanying commentary, in the book Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000.

1900년에 2000년이 어떤 모습일지를 상상하기 위해 제작된 이 종이 카드들은 처음에는 리옹의 프랑스 장난감 제조업자 아르망 제르베가 파리 세계 박람회를 위해 의뢰했다. 장-마르크 코테가 제작한 첫 50장의 카드는 담배 상자 안에 넣어지기도 하고, 나중에는 엽서로 발송되기도 했다. 코테와 다른 예술가들은 총 78장 이상의 카드를 제작했으며, 정확한 수는 알려져 있지 않고 일부는 아직 발견되지 않았을 수도 있다. 각각의 카드는 당시로서는 먼 미래인 2000년에 살게 될 것이 어떤 모습일지를 상상하려고 시도했다.

일부 기술은 놀랍도록 예지력이 있었다. 기계로 닭알을 부화시키고, 재단은 부분적으로 자동화되었다. 대중은 전자 음악을 위해 교향악단에 모였다. 가장 정확한 묘사는 전쟁터와 산업 농업의 극장에서 찾아볼 수 있는데, 이는 20세기를 통틀어 기술 발전의 주요 경제적 동력이었음을 증명한다: 자동차에 부착된 개틀링 총, 비행선 같은 전함, 콤바인 수확기로 자른 밭들. 종종 그렇듯이, 다른 예측들은 현재의 기술 환경의 제약을 벗어나는 것에 실패하여, 목표에 다소 미치지 못했다(따라서 프로펠러의 만연, 라듐 벽난로, 뚜렷한 19세기 복장이 등장한다). 그 외에도 빠른 해양 정복을 예상한 예측들은 이상하게 남아 있다: 해수면에서 갈매기를 쫓는 잠수부 다이버, 수중 크로켓, 고래 버스(말 그대로의 의미).

이러한 다소 예지력 있는 장면들은 그들의 미래가 거의 현실이 될 무렵까지 세상의 빛을 보지 못했다. 제르베가 1899년에 몇 세트의 카드를 인쇄했지만, 제작 중에 사망했다. 이어지는 25년 동안, 카드들은 그의 폐업한 장난감 공장 지하실에 미래의 비전처럼 잊혀진 유물들과 함께 먼지를 쌓았다. 한 골동품상이 아카이브를 구입하여 자신의 지하실로 옮겼고, 그곳에서 50년 더 보관되었다. 그 후 캐나다 작가 크리스토퍼 하이드가 파리의 그의 가게에서 이들을 우연히 발견했다. 하이드는 차례로 이 카드들을 과학 소설 작가 아이작 아시모프에게 빌려주었고, 아시모프는 1986년에 이 카드들을 다시 출판하고, Futuredays: A Nineteenth Century Vision of the Year 2000라는 책에 덧붙여진 해설과 함께 발행했다.